Most conversations about AI-generated malware still sound like a trailer for a dystopian film. Self-driving attacks. Machines picking targets. Autonomous chaos.

VoidLink is a useful antidote to that kind of thinking.

Not because it’s harmless, and not because it’s already everywhere. It’s useful because it shows something more real, and more immediate: what happens when a skilled operator uses generative AI as a force multiplier, not a gimmick. Suddenly, the limiting factor isn’t time, team size, or even tooling maturity. It’s whether the attacker knows what they’re building, and how to get there fast.

That’s why VoidLink matters. It doesn’t need a headline-grabbing breach to change the conversation. It’s proof that fully AI-generated malware development isn’t theoretical anymore. It’s an emerging production model, and it’s already capable of turning cloud-native Linux environments into a long-term hunting ground.

Why VoidLink Is a Turning Point, Not Just Another Malware Discovery

Most malware write-ups boil down to two questions: who got hit, and how bad was it?

VoidLink flips the order of importance.

The most striking detail from the research isn’t a list of victims. It’s the level of maturity on display at an early stage. You’re looking at a framework, not a one-off payload. A system built to maintain long-term access. A design that assumes the target environment is modern, monitored, containerised, and operationally noisy. And a toolchain that looks like it’s meant to be used, refined, and scaled over time.

That’s why VoidLink sits in a different category from typical Linux malware. It behaves less like an opportunistic implant and more like an advanced post-exploitation framework engineered for cloud infrastructure. It’s built around staying power, not spectacle.

If you’re responsible for cloud infrastructure security, the uncomfortable takeaway is simple: you can’t rely on the idea that Linux threats are usually rough around the edges, or that sophisticated toolsets are reserved for a handful of big groups. VoidLink challenges both assumptions.

What Makes VoidLink Different From Traditional Linux Malware

VoidLink isn’t “advanced” because it has one clever trick. It’s advanced because it combines a lot of hard problems into a cohesive system, and it does that in a way that feels deliberate.

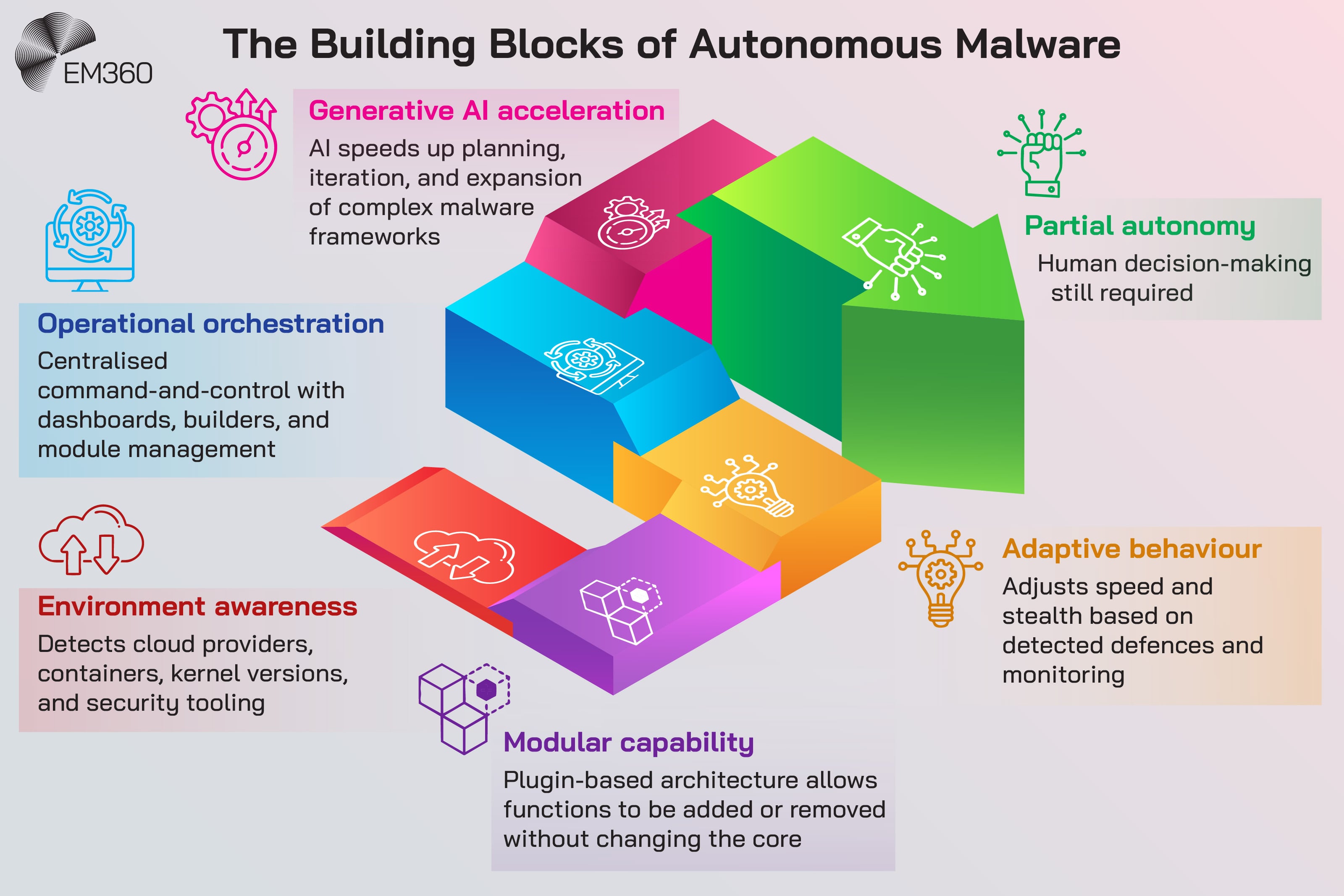

Built for cloud and container environments from day one

VoidLink is cloud-first by design. The research describes a framework that can recognise major cloud environments and detect whether it’s running in Kubernetes or Docker. That matters because modern enterprises don’t run Linux in neat little boxes anymore. Linux runs the workloads. The workloads run the business.

Once a threat understands cloud and container context, it can do more than steal a file or run a command. It can shape its behaviour around the environment it’s in. It can target the places where secrets live, where credentials get cached, and where engineering teams move fast and sometimes a little too trustingly.

This is also where cloud-native malware becomes a business risk multiplier. One compromised workload can become a launchpad into clusters, pipelines, and identities that weren’t meant to be connected in the first place.

A modular architecture designed to evolve quietly

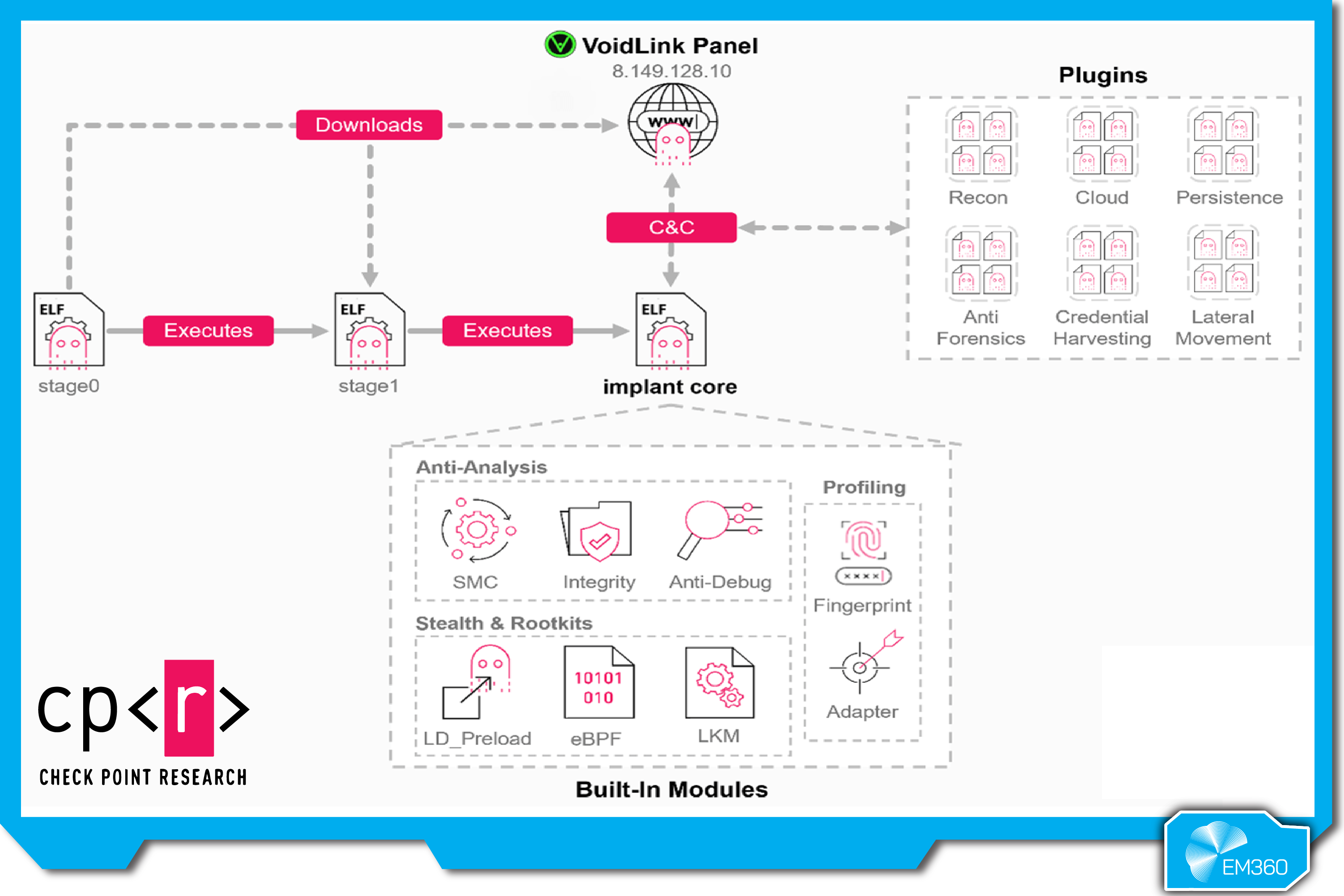

VoidLink’s modularity is one of its loudest signals of intent.

Instead of shipping as a single, static tool, it’s built around a plugin system and a custom development Application Programming Interface (API). In plain terms, that means the core implant can stay stable while the attacker adds capabilities as needed, without rewriting the whole thing.

This is where the “framework” label matters. A modular Linux malware framework can start small, stay quiet, and expand only when it’s safe. Reconnaissance today. Credential access tomorrow. Lateral movement next week. Anti-forensics when the operator thinks they’re done.

When Tech Shocks Become Strategy

What bizarre innovations reveal about how AI, cloud and the metaverse quietly reset digital priorities in boardrooms.

If you’ve dealt with the abuse of legitimate tools like Cobalt Strike, the pattern will feel familiar. A consistent core. Extensible modules. Operator control. Repeatable workflows.

That repeatability is what turns a single operation into a scalable threat.

Adaptive stealth and operational security by design

Plenty of malware tries to hide. VoidLink goes further by treating stealth as a living strategy.

The research describes behaviour that adapts based on what the malware detects in the environment, including security tooling and hardening measures. If monitoring is present, it slows down and prioritises evasion. If visibility is limited, it can move more freely.

That’s a practical kind of sophistication. It’s not about being invisible in an absolute sense. It’s about being quieter than everything else in an environment that’s already full of noise.

VoidLink also includes techniques associated with rootkits, including user-mode approaches and kernel-level paths. You don’t need to memorise the mechanics to understand the impact. If a tool can hide processes, files, and network activity, then “we didn’t see anything” stops being reassuring. It becomes part of the threat model.

Add runtime protection and anti-tampering behaviour, and you start to see a framework that’s built to survive scrutiny, not just survive execution.

The Command-and-Control Platform Signals Productisation

Malware usually tells you what it is by how it’s operated.

VoidLink reportedly ships with a web-based command-and-control dashboard, including a builder and plugin management. That matters because it points to product thinking.

A dashboard isn’t just convenience. It’s an operational control plane. It’s how an attacker standardises workflows, manages multiple implants, tunes behaviour, and deploys new modules without a rewrite. It’s also how you make a tool usable by someone other than its original developer, even if that “someone” is just the same operator in a different campaign.

AI Power Brokers to Watch

From Microsoft–OpenAI to Google Gemini, meet the leaders directing capital, talent and roadmaps in the most contested tech arena.

This is where cloud-native malware becomes a strategic concern. When tooling starts to look like an ecosystem, defenders should assume it’s meant to last. Not as a one-time experiment, but as a platform that can be iterated on until it fits the real world perfectly.

And if the research is right that this is evolving quickly, then “early-stage” doesn’t mean “immature.” It means “still gaining features.”

AI as a Force Multiplier in Malware Development

This is the part that needs discipline, because it’s easy to slip into hype.

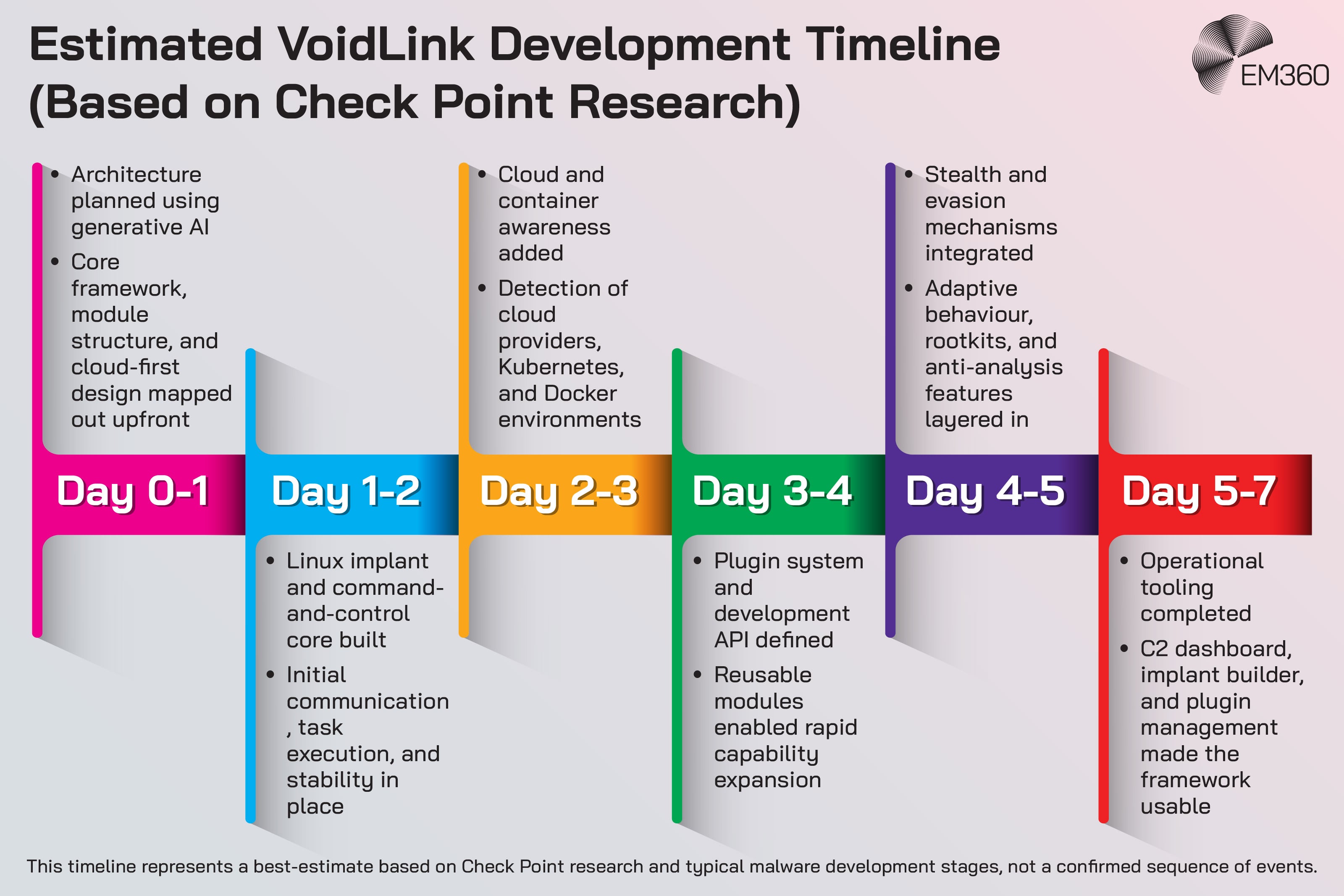

VoidLink isn’t being positioned as an autonomous, AI-run attack. The more credible claim is simpler: generative AI helped accelerate the creation of a complex malware framework that looks like it would normally require a larger team and a longer timeline.

That’s still a big deal.

From months to days: how AI compressed the development lifecycle

The most useful way to think about AI here isn’t “AI wrote the malware.” It’s “AI helped the operator build like a team.”

Planning. Specifications. Deliverables. Testing. Iteration. Documentation. The tedious parts that slow development down, and the scaffolding that keeps a large project coherent.

Those are exactly the areas where AI can speed things up for someone who already knows what they’re doing. It can draft code patterns. It can refine syntax. It can help troubleshoot. It can generate structured plans and keep the moving parts aligned.

That’s what changes the economics of malware development. Not because AI creates genius attackers overnight, but because it removes friction. It compresses time. It makes complex builds more achievable at a faster pace.

That’s the real meaning of AI-generated malware in this context. The pipeline has changed.

Why this still required real expertise

Here’s the part worth saying out loud, because it keeps the conversation honest.

Aurora’s Safety and IP Exposures

Examines X’s content training terms, Aurora’s handling of copyrighted and graphic imagery, and the governance gaps that could trigger regulatory heat.

A framework like VoidLink doesn’t emerge from AI alone. It reflects deep knowledge of Linux internals, cloud environments, and operational tradecraft. It pulls together multiple components that have to work reliably in messy, real systems. That isn’t something a novice gets right by prompting harder.

Generative AI can accelerate capability, but it can’t replace judgement. It can’t invent experience. It can’t teach an operator how to think like an attacker or how to build for stealth and persistence in monitored environments.

So yes, AI lowers barriers. But it lowers them most for people who already have the skills to clear them.

The Single-Operator Insight Changes the Threat Model

This is where VoidLink stops being “one malware story” and starts feeling like an uncomfortable shift in the threat landscape.

If the research is correct that this appears to be the work of a single operator, it doesn’t reduce the threat. It multiplies it.

When one person can replicate a team

Security teams have always tracked the big players. Well-resourced groups. Established operations. Tooling that suggests a coordinated effort.

But if one skilled individual can use AI to replicate the pace and structure of a team, then the old shorthand becomes less useful. Team size stops being a reliable indicator of capability. “It looks too mature to be one person” stops being a comforting assumption.

AI doesn’t just accelerate code. It reduces coordination overhead. No meetings. No handoffs. No waiting for a different specialist to solve a different piece of the puzzle. One operator can keep momentum, iterate quickly, and ship features at speed.

That’s a different kind of scalability.

Why every experienced group member becomes a potential independent threat

There’s also a quieter implication that’s worth taking seriously.

AI Imagery Reshapes Workflows

Text-driven image generation is compressing design timelines and changing how organizations plan, test and scale visual content output.

Threat groups aren’t made up of one competent person and a crowd of bystanders. They’re made up of people with overlapping skills, shared methods, and operational experience. If the barrier to building sophisticated frameworks drops, then a group doesn’t represent one threat. It represents many credible threats, each capable of going solo.

Not all of them will. But the possibility changes how defenders should think about proliferation.

It’s not only about new malware families appearing. It’s about the same quality of tradecraft showing up in more places, from more actors, with less warning.

That’s what attacker decentralisation looks like when AI enters the development pipeline.

VoidLink Is Not Autonomous, But It Shows How Close the Building Blocks Are

It’s important to be precise here.

VoidLink is being described as AI-generated in the sense of its development, not in the sense of autonomous decision-making in the field. There’s still an operator. There’s still human intent. There’s still a command-and-control loop.

But it also shows how much of the groundwork is already in place for more automation.

A modular plugin system is automation-friendly. A risk-scoring approach to stealth is automation-friendly. A builder that tunes behaviour is automation-friendly. A dashboard that manages workflows is automation-friendly.

If you’re in cybersecurity, you’ve probably heard the same question repeatedly: when will we see more agentic behaviour, where tools chain actions and adapt without a human driving every step?

VoidLink doesn’t answer that question directly. What it does do is make the concern feel less hypothetical. It’s a reminder that “not autonomous” doesn’t mean “not advancing toward automation.” It means the operator still has the wheel, for now.

What VoidLink Signals About the Future of Cloud and Linux Security

VoidLink isn’t just about AI. It’s also about where attackers are investing their effort.

Linux workloads and cloud infrastructure are where critical services live. They’re where identity, data, and uptime intersect. And they’re often defended unevenly, especially when organisations treat them as “infrastructure” rather than as high-value targets in their own right.

A cloud-first implant makes that bias visible. It assumes the cloud is a primary attack surface, not an extension of the data centre. It assumes container environments are worth specialising for. It assumes credentials and secrets are the prize.

It also reinforces a reality a lot of organisations are still catching up to: workload security and identity security are increasingly inseparable. If an attacker can establish long-term access inside Linux cloud workloads, they’re not only sitting on compute. They’re sitting near the paths that lead to data stores, pipelines, service accounts, and developer tooling.

And if AI accelerates the creation of these frameworks, defenders will see more variation, more rapid iteration, and less time to adjust between “first sighting” and “operational use.”

That’s the pressure point. Speed.

What Security Leaders Should Take From VoidLink Right Now

VoidLink doesn’t demand panic. It demands a sharper mental model.

First, don’t treat “AI-driven threats” as a future problem just because autonomy isn’t proven. The development pipeline has already changed. That alone increases the pace at which new capabilities can enter the ecosystem.

Second, don’t underestimate Linux and cloud workloads because Windows remains the loudest battlefield. Attackers follow value. In many organisations, the value lives in cloud services and the identities that operate them.

Third, be wary of relying too heavily on attribution or assumptions about resourcing. If high-end tradecraft can come from a single operator, and if AI makes that more feasible, then capability will show up in more places, from more directions.

Finally, prioritise visibility and resilience over perfect prediction. Frameworks like VoidLink are built for long-term access, not quick disruption. That means the question isn’t only “can we block it?” It’s also “can we notice it?” and “can we contain it when we do?”

If your cloud environment is a black box, you’re not defending it. You’re hoping it behaves.

Final Thoughts: AI Has Changed Who Can Build Advanced Malware

VoidLink is a reminder that the most dangerous shifts in cybersecurity don’t always arrive with fireworks. Sometimes they arrive as a well-engineered framework that hasn’t even been widely deployed yet.

The lesson isn’t that AI is about to unleash fully autonomous malware tomorrow. The lesson is that AI is already reshaping how advanced threats get built, who can build them, and how quickly they can iterate. A single skilled operator with the right tools can now move with the momentum of a team, and that changes the pace of the threat landscape more than any single infection ever could.

The future here isn’t just more malware. It’s faster malware development, more modular capability, and more credible threats emerging from unexpected places. The organisations that stay steady won’t be the ones chasing every headline. They’ll be the ones building clear visibility into their cloud and Linux environments, then making decisions based on what’s real, not what’s loud.

That’s the kind of grounded sense-making EM360Tech is here for. Just the strategic clarity security leaders need to stay ahead of what’s changing, and what’s already changed.

Comments ( 0 )