Infrastructure has always been where strategy meets reality. It's where bold transformation plans either become dependable services or turn into a late-night incident channel and a spiralling bill.

In 2025, long-standing assumptions finally cracked. Not because infrastructure teams forgot how to run environments, but because the ground shifted under the models those environments were built on. Cost stopped behaving like a predictable optimisation problem. Power became a physical limiter.

Outages exposed how many critical layers sit outside any one provider’s control. Multicloud connectivity moved from “possible” to operational. Visibility became a prerequisite, not a nice-to-have.

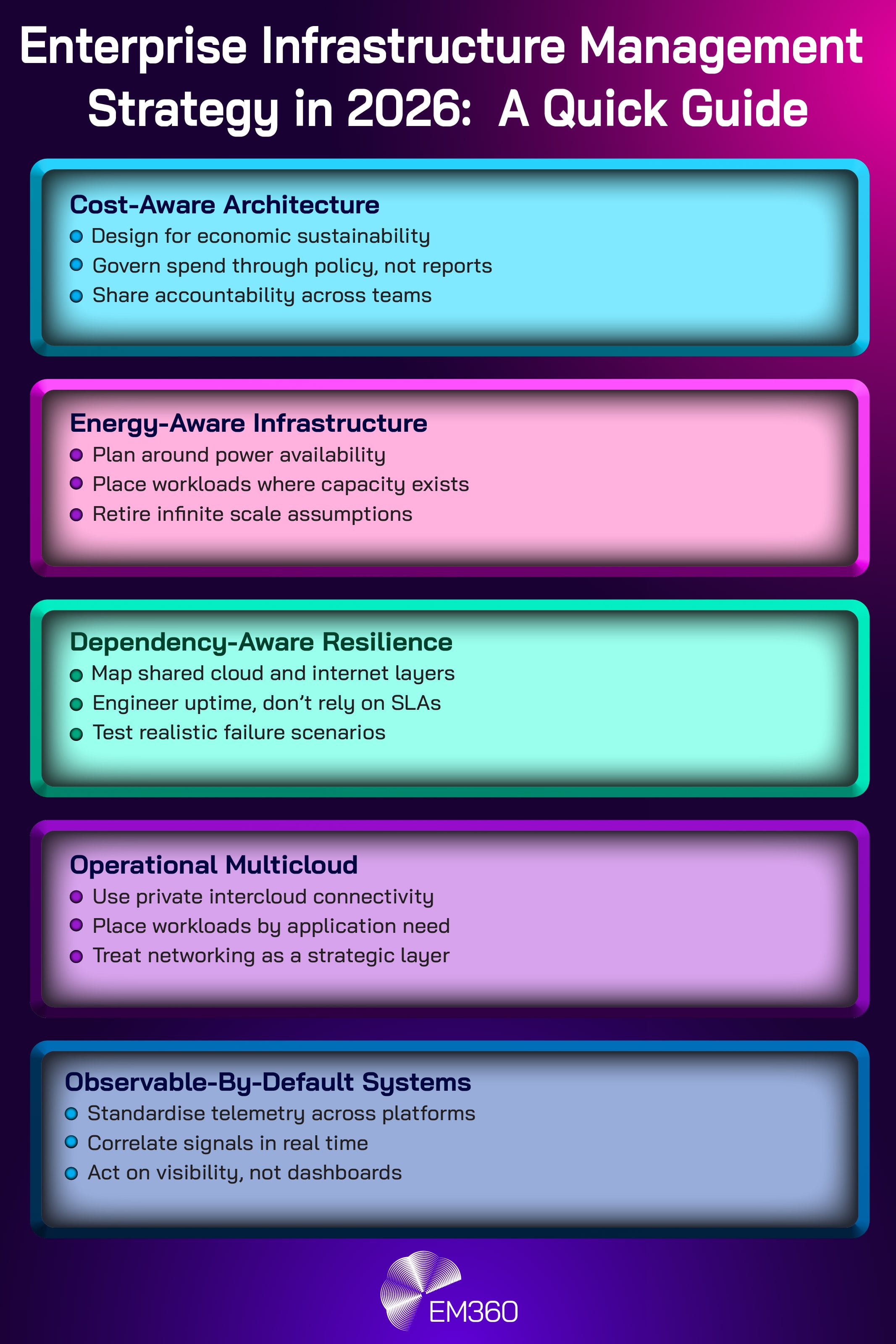

All of this points to the same direction. In 2026, infrastructure management will be less about chasing scale and more about designing within constraints, mapping dependencies, and governing behaviour across cloud and on-prem infrastructure.

Infrastructure Spend Became a Governed Risk, Not a Passive Cost

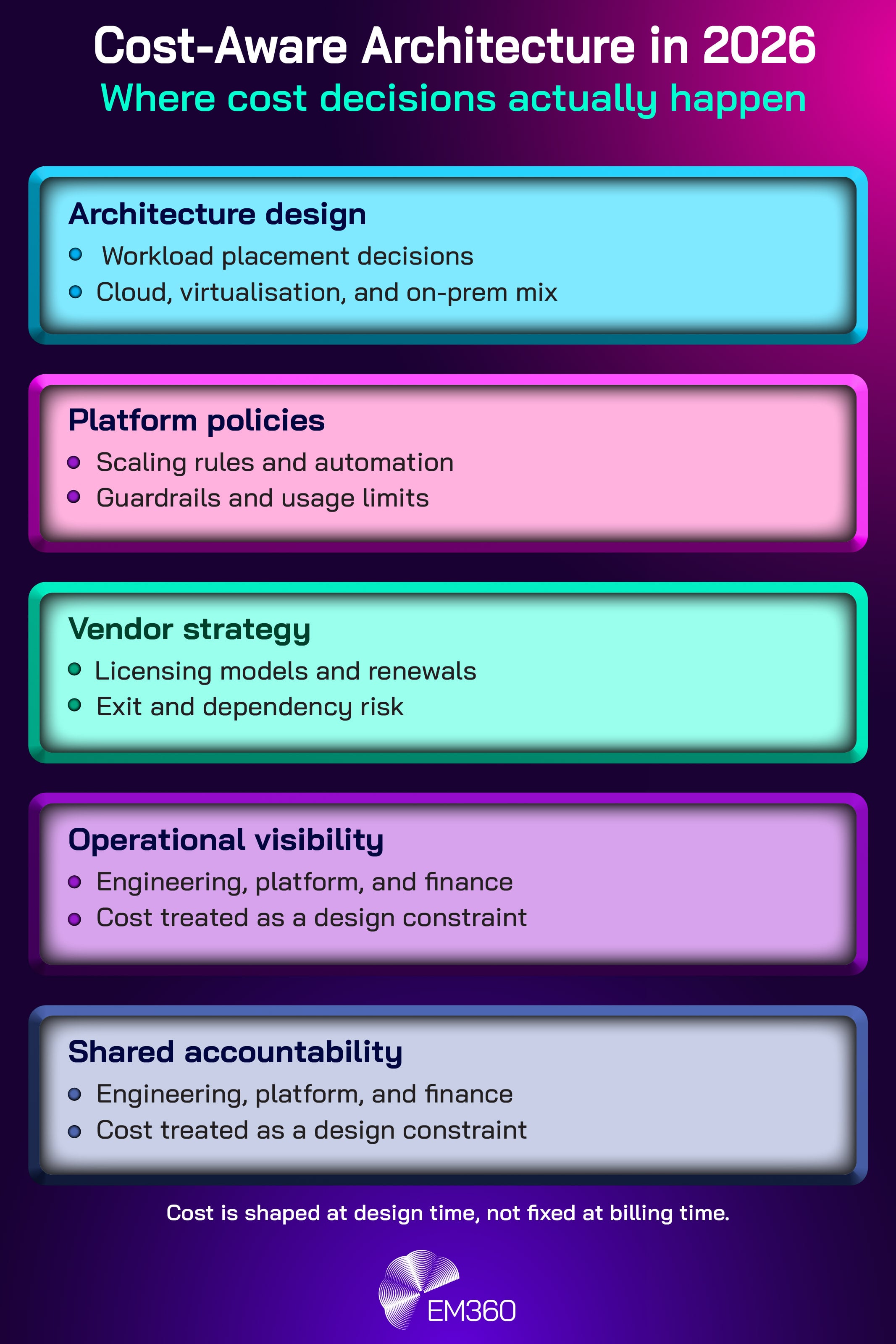

Infrastructure spend has always been monitored, but 2025 forced it into the category of governed risk. The biggest accelerant was commercial shock. VMware’s licensing and packaging changes following Broadcom’s acquisition pushed many enterprises to revisit renewal assumptions, virtualisation roadmaps, and the pace at which migration plans could realistically happen.

At the same time, cloud consumption became harder to predict. Workloads driven by data pipelines, analytics and artificial intelligence (AI) don't always scale in neat lines, and they don't always behave like the steady-state applications most cost models were built around. Consumption volatility made it clear that “we’ll optimise later” isn't a strategy, it's a liability.

That shift also showed up in the language of modern operating models. The FinOps Foundation expanded its framework to reflect a broader reality where spend spans public cloud, software-as-a-service (SaaS), virtualisation, AI platforms, and on-prem estates. Cloud+ is the important signal here. It acknowledges that infrastructure economics now lives across multiple environments, not in a single cloud billing console.

How enterprises responded in the moment

The first reaction was uncomfortable honesty. Many organisations realised their biggest infrastructure cost exposures were not caused by inefficient engineers, but by structural dependency. Vendor concentration, licensing models, and renewal cycles can lock enterprises into cost patterns that no dashboard can fix.

Cost governance also moved closer to architecture. Teams began asking questions that would have felt “too financial” a few years ago. Where are we exposed to contract risk? Which platforms are hard to exit? Which workloads are expensive because of design choices rather than usage peaks?

FinOps, defined as a discipline for managing cloud financial operations, also stopped being a reporting role and became a coordination role. FinOps expanded into procurement, platform engineering, and decision-making guardrails. The focus shifted from after-the-fact reporting to shaping behaviour before spend happens.

Why infrastructure planning in 2026 starts with economic sustainability

In 2026, cost stops being a quarterly exercise and becomes a design constraint. The more mature organisations will treat economic sustainability the way they treat security and resilience: as a non-functional requirement that must be met before scale is approved.

This is where cost-aware architecture becomes the default. Workload placement, scaling policies, and platform choices will be justified not only by performance and reliability, but by whether they can remain viable at enterprise scale without constant emergency optimisation.

The operational change is subtle but decisive. Budgets will increasingly fund continuous governance, not one-off savings programmes. Platform teams will be expected to build guardrails that prevent runaway consumption. Finance will be part of the operating model, not only part of the approval process.

Infrastructure economics becomes everyone’s responsibility, because the risk belongs to the whole organisation.

Power and Energy Constraints Defined the Real Limits of Scale

Why Observability Now Matters

How telemetry, tracing and real-time insight turn sprawling microservices estates into manageable, high-performing infrastructure portfolios.

2025 put a hard boundary around a long-held assumption: that compute can always be provisioned somewhere, if you’re willing to pay for it. AI-era demand pushed data centre capacity into a new conversation, one shaped by electricity supply, cooling capability, and grid connection timelines.

This isn't only a hyperscaler problem. Enterprises building private cloud capacity, expanding colocation footprints, or trying to secure AI-ready infrastructure ran into the same reality. Power availability can delay builds, constrain regional growth, and make “where should this run?” a question that has a physical answer.

Sustainability pressures also stopped sitting in a separate lane. Energy use and emissions targets began colliding directly with infrastructure expansion plans. That collision is operational. It affects procurement, location strategy, and the ability to deliver on transformation roadmaps.

How enterprises responded in the moment

The immediate response was planning recalibration. Capacity planning began to extend beyond service catalogues and cloud region maps. Organisations started considering power access as a first-order constraint.

For some, that meant revisiting provider strategy, not from a cost perspective, but from an availability perspective. For others, it meant reassessing how much of their “AI readiness” was real, and how much depended on capacity that might not materialise on the expected timeline.

The second response was a sharper focus on efficiency. Efficiency stopped being a moral goal and became a delivery requirement. When power is limited, every wasted watt is effectively lost capacity. That pushes optimisations like right-sizing, improved scheduling, and workload placement into the category of business continuity.

Why infrastructure growth models in 2026 are explicitly energy-aware

In 2026, infrastructure teams will treat energy constraints the way they treat latency or regulatory requirements. They'll be part of architecture decisions, not an afterthought. “Infinite scale” will quietly disappear from planning models, replaced by forecasting tied to real-world availability.

That shift will show up in workload placement. Organisations will start asking where workloads should run based on energy efficiency, capacity certainty, and cooling viability, not only on performance and cost. Provider selection will increasingly consider power access and expansion feasibility as differentiators.

Inside Unified Cloud Control Planes

A board-level look at platforms that knit FinOps, SecOps and CloudOps into one layer to manage hybrid estates at enterprise scale.

It also changes what “resilience” means. If a region is constrained by energy supply, then rapid expansion during peak demand or incident response may not be possible. Resilience planning becomes more conservative and more realistic, because it has to be.

Cloud and Internet Dependence Became an Architecture Responsibility

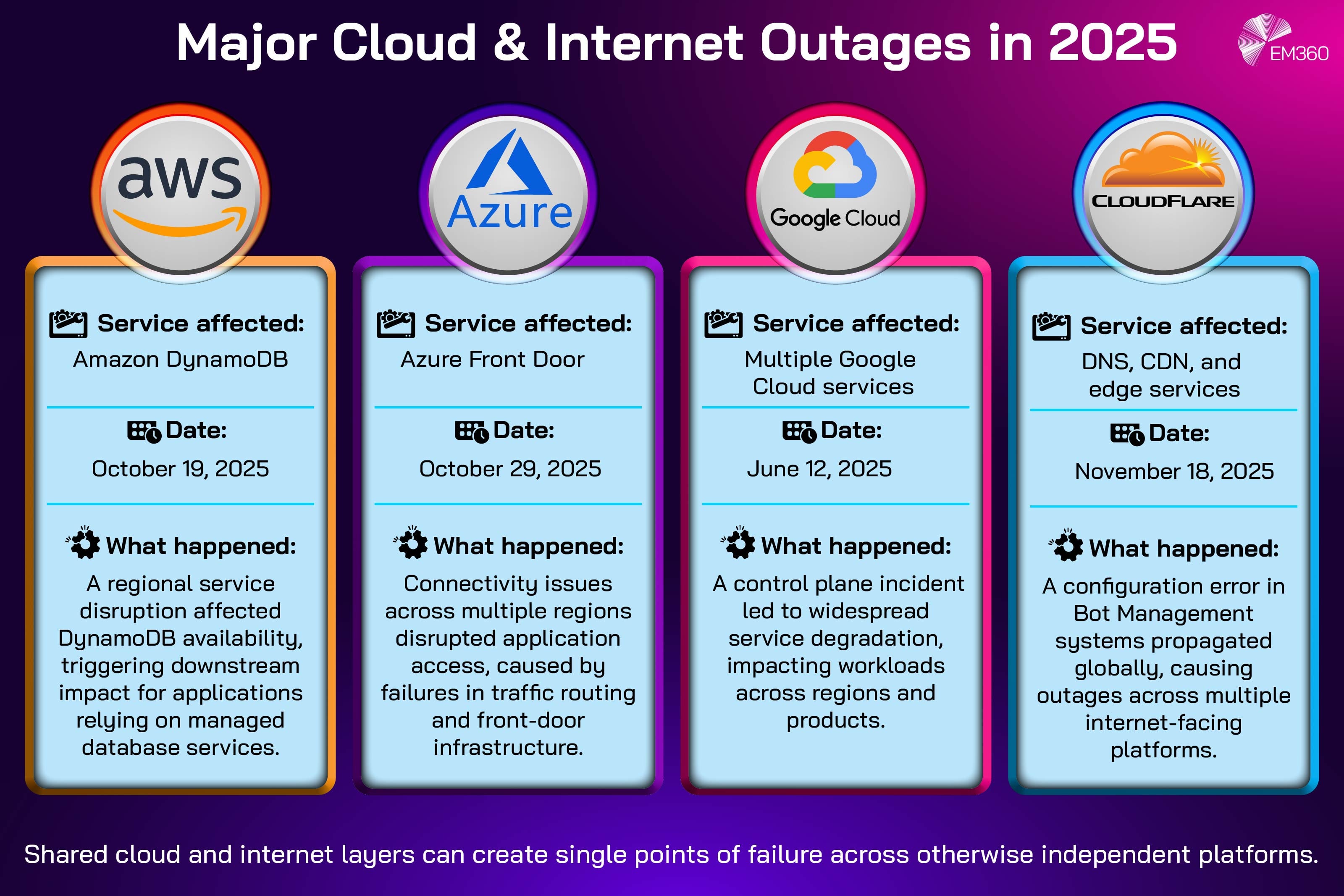

Outages were not new in 2025, but the pattern of outages was. The year delivered high-impact incidents across hyperscalers and shared internet layers. AWS reported a significant disruption involving Amazon DynamoDB in October 2025.

Microsoft published a post-incident review for Azure Front Door connectivity issues affecting multiple regions on October 29, 2025. Google Cloud recorded a major multi-product incident on June 12, 2025. Cloudflare published an outage analysis for a broad service impact event on November 18, 2025.

Taken together, these incidents made one thing undeniable. Enterprises don't only depend on a single cloud provider’s compute and storage. They depend on front doors, identity services, control planes, configuration systems, and internet-layer services like Domain Name System (DNS) and Content Delivery Network (CDN) capabilities.

And many of these layers are shared across multiple platforms.

How enterprises responded in the moment

The first response was reframing. Resilience could no longer be treated as something purchased through a service level agreement (SLA). It became something designed through architecture. That isn't a philosophical shift, it's a responsibility shift.

Enterprises began expanding dependency mapping. It was no longer enough to say, “this application runs on Azure” or “we are an AWS shop”. Teams started documenting what sits in front of critical services, what those services rely on, and what failure modes are realistic.

Incident response matured in parallel. Post-incident reviews increasingly asked architectural questions. Where are we coupled to a single control plane? Which services fail together? Which dependencies are invisible until they break?

Why uptime in 2026 is something enterprises engineer, not purchase

In 2026, cloud dependency risk will be treated like a design input, not a post-incident lesson. The goal will not be blanket multicloud, because that can create its own complexity. The goal will be selective resilience.

Managing AI Complexity at Scale

Why the next wave of enterprise value hinges on pairing observability data with generative AI to govern risk and automate decisions.

That can look like multi-region by default for critical services, or selective multi-provider strategies for high-impact dependencies. It will also look like resilience testing that includes internet-layer failures, not only application failures. Runbooks will be written around credible shared-layer scenarios, because those are the ones that create unexpected blast radius.

The mindset shift is simple. Uptime stops being a number on a contract and becomes a capability an organisation builds.

Multicloud Networking Became an Operational Capability

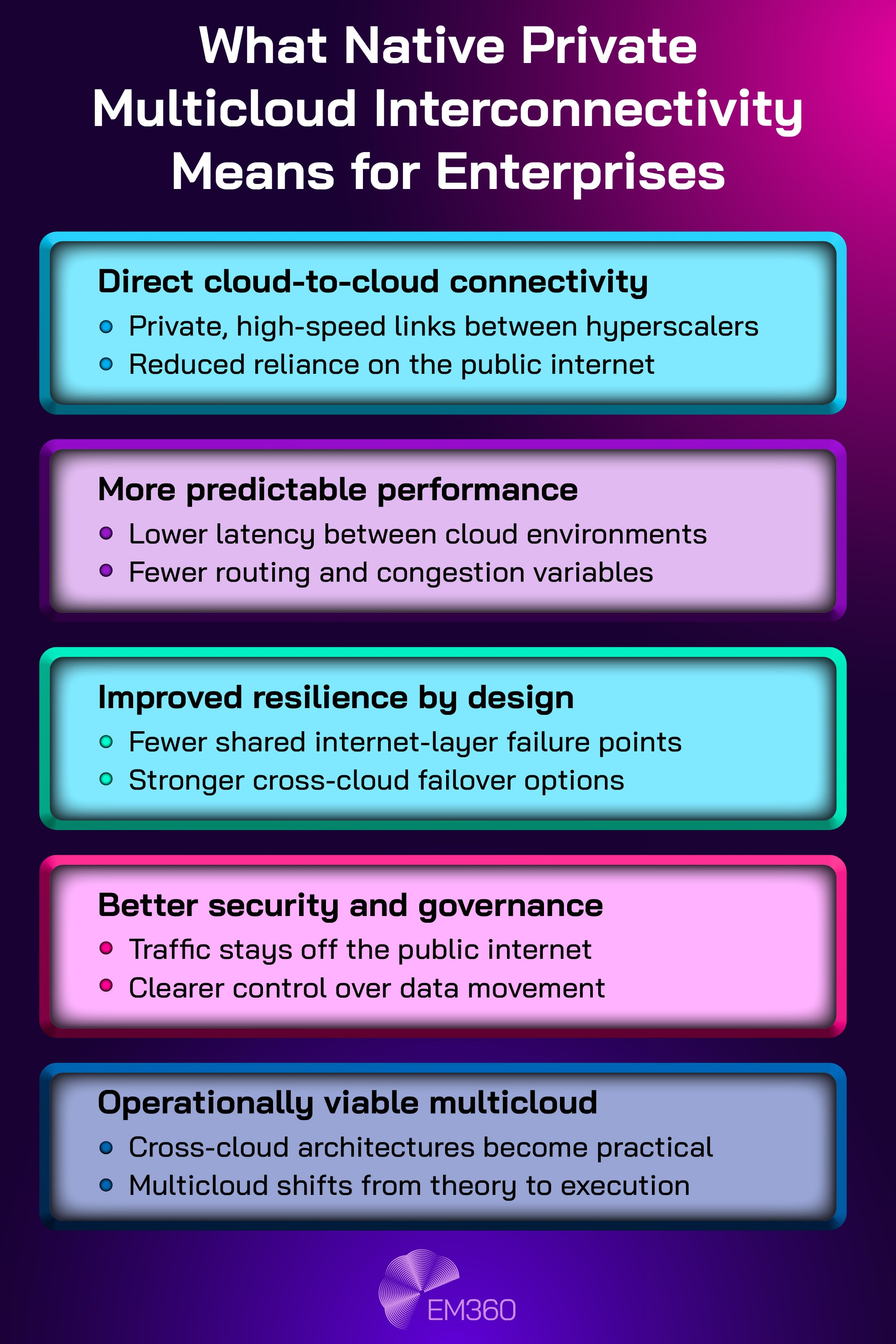

Multicloud has been discussed for years, often as a strategic ideal and a technical headache. A large part of the headache has been networking. Moving data securely and predictably across cloud boundaries has historically relied on the public internet, complex third-party overlays, or bespoke arrangements that are hard to operate at scale.

In December 2025, AWS and Google Cloud launched a jointly engineered approach to private multicloud connectivity. The practical point isn't marketing. It's operational. Provider-supported private links between major clouds reduce latency variability, increase predictability, and make cross-cloud architectures less fragile.

This matters because networking is often the hidden limiter in multicloud. If networking is unstable, everything else inherits the risk.

How enterprises responded in the moment

The enterprise reaction was not excitement, it was reassessment. Organisations that had dismissed multicloud as too complex began revisiting where it might be worth it. Data-intensive workloads, cross-cloud disaster recovery patterns, and regulated data transfers are all use cases where predictable private connectivity changes the feasibility equation.

Networking also moved up the architecture stack. Multicloud is often framed as a platform decision, but 2025 reminded teams that it's equally a network decision. If data can't move reliably across boundaries, the architecture is theoretical.

Why multicloud strategy in 2026 becomes application-led, not philosophical

In 2026, multicloud networking will be treated less as an ideology and more as an application-level capability. The question will not be “should we be multicloud?” but “which applications benefit from cross-cloud placement, and what does it cost to run that reliably?”

Why AIOps Now Leads IT Strategy

How AI-driven operations move IT from reactive firefighting to predictive, self-healing services across complex hybrid and cloud environments.

This is where private connectivity becomes a foundational layer. Budget lines appear for intercloud links. Architecture assumptions shift toward secure multicloud backbones for the workloads that justify them. Networking becomes a strategic enabler rather than plumbing that gets figured out late.

The deeper implication is that infrastructure management becomes more orchestration-driven. When connectivity is predictable, workload placement becomes a tool for resilience, performance, and governance. When it's not, multicloud remains a slide deck.

Infrastructure Complexity Forced Observability to Standardise

Infrastructure complexity crossed a threshold in 2025. Enterprises were managing estates spread across multiple cloud platforms, internet services, on-prem systems, event-driven architectures, and increasingly automated workflows. The more distributed the environment becomes, the less useful fragmented monitoring becomes.

Traditional monitoring assumptions also broke down. Event-based systems and AI-driven components don't always produce predictable request paths. Failure signals can be subtle, distributed, and fast-moving. When logs, metrics, and traces are siloed across tools and teams, incident response becomes guesswork.

That is why the momentum toward standardised telemetry accelerated. OpenTelemetry, an open standard for collecting and exporting telemetry such as logs, metrics, and traces, became a practical response to fragmentation. The goal was not better dashboards. It was shared visibility across layers.

How enterprises responded in the moment

The enterprise response was enforcement. More organisations began treating consistent instrumentation as a platform requirement, not an optional improvement. If a service can't produce usable telemetry, it's harder to operate safely.

Teams also started linking observability to broader governance goals. Cost governance requires visibility into what is consuming resources and why. Resilience requires the ability to trace failures end to end. Capacity planning requires trusted signals. Fragmented monitoring blocks all of them.

This is the moment where observability stopped being a tooling preference and became part of infrastructure plumbing.

Why infrastructure management in 2026 assumes observable-by-default systems

In 2026, the baseline expectation will shift. Systems will be expected to be observable by default, with common telemetry standards across environments and providers. That is the only way to make distributed infrastructure manageable at enterprise scale.

The operational payoff is speed and certainty. Faster root cause analysis. Clearer blast radius mapping. Better correlation between incidents, cost spikes, and capacity constraints. More importantly, observability becomes a prerequisite for decision-making, not a retrospective reporting tool.

The question also changes. It's no longer “do we have visibility?” It becomes “do we have visibility we can act on, quickly, across the whole estate?”

Final Thoughts: Infrastructure Strategy Is Now Defined by Constraints

The unifying lesson of 2025 is that infrastructure is no longer defined by what teams can provision, but by what they can govern. Cost volatility made spend a risk to manage, not a number to track. Power availability exposed physical limits to growth.

Outages proved that resilience is an architectural responsibility across shared layers. Private multicloud connectivity made cross-cloud operations more practical. Standardised telemetry became the foundation for managing complexity.

In 2026, the organisations that move fastest will not be the ones chasing infinite scale. They'll be the ones designing within constraints on purpose, mapping dependencies honestly, and building operating models that treat governance as a core capability.

If 2025 was the year assumptions broke, 2026 is the year infrastructure leadership gets measured by what replaces them. EM360Tech will keep tracking the shifts that matter most to enterprise teams, not as noise, but as signals you can use to steer architecture, operations, and investment with more confidence.

Comments ( 0 )