Enterprise security conversations have spent the last few years moving up the stack. Identity-first access, Zero Trust, and Secure Access Service Edge (SASE) have changed how leaders think about access. Who gets in. Under what conditions. And why.

That change was necessary. It was overdue. And in many ways, it worked.

But at the same time, critical connectivity barely moved.

Remote access, site-to-site links, partner connections, and hybrid cloud paths are still built on protocols standardised long before today’s access models existed. They work. They’re encrypted. They’re familiar. That familiarity is exactly why they rarely get close attention once they’re in place.

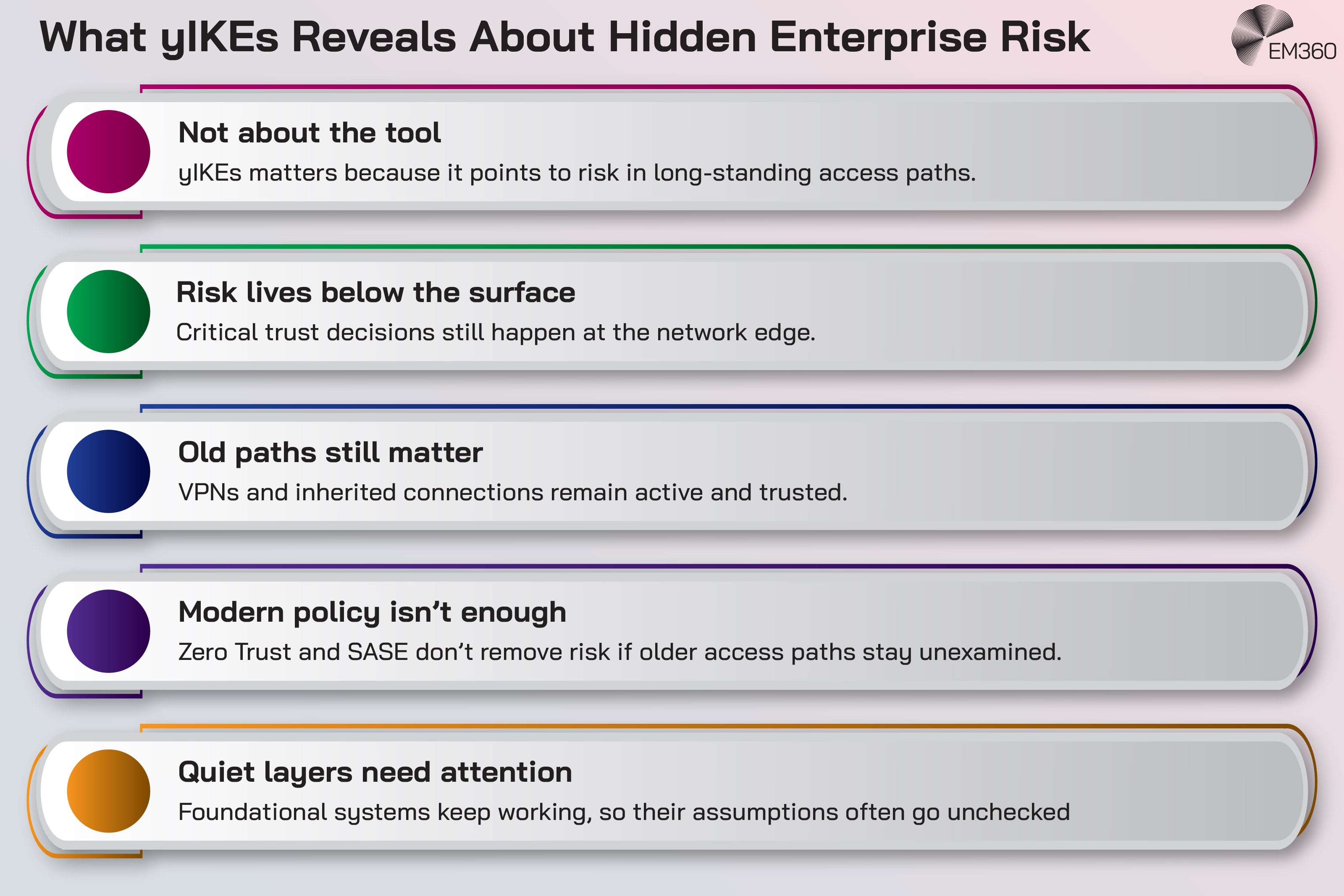

The renewed focus on yIKEs exposes that gap. It isn’t interesting because it’s new. It’s interesting because it pulls attention back to the network edge. And to assumptions many organisations haven’t challenged in years.

What yIKEs Actually Is (And Why That’s Not the Point)

At a basic level, yIKEs is an open-source security assessment tool used to test implementations of Internet Key Exchange version 2 (IKEv2). Its focus is how authentication is handled during the exchange.

So it doesn’t actually protect anything. It just observes behaviour.

That distinction matters. Not because most enterprises need to run the tool, but because of what it’s designed to examine.

A plain-English explanation of IKE, IKEv2, and IKE_AUTH

Before we go any further, we need to explain some terminology. Because the meaningful acronym here isn’t yIKEs. It’s IKE.

Internet Key Exchange (IKE) is the process used to set up cryptographic keys for Internet Protocol Security (IPsec), which is commonly used to secure VPN connections. IKEv2 is the widely used version of that protocol. And it’s the foundation of a large share of encrypted traffic across VPNs, branch networks, cloud environments, and partner links.

From a leadership view, IKEv2 does two critical things. It creates encrypted tunnels. And it confirms that the systems on either end are allowed to use them.

The IKE_AUTH phase is where that trust is enforced. Authentication finishes here. The first IPsec security association is created here. This places IKE_AUTH directly between encryption and access.

When this stage behaves in unexpected ways, the impact is real. It affects who can create tunnels. It affects when access is granted. And it affects what the network trusts by default.

That’s why this layer is still worth testing, even in modern environments.

Why this obscure tool is suddenly being talked about

Protocol-level tools don’t resurface without a reason. It usually follows a moment where long-trusted infrastructure suddenly needs to be scrutinised. And that’s usually because a real exploit exposes just how much of your network relies on that layer.

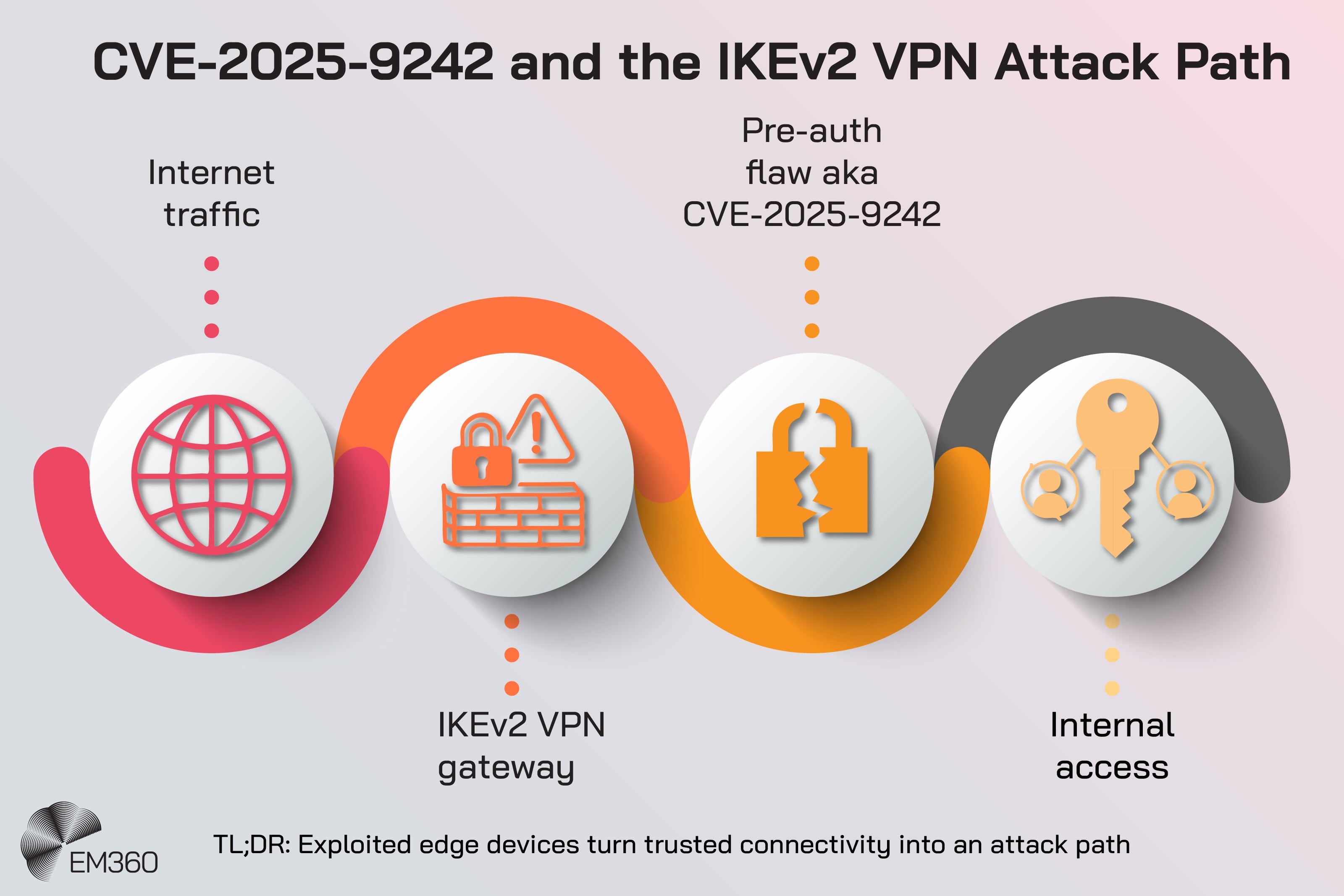

In this case, attention returned after the disclosure and exploitation of an IKEv2-related vulnerability affecting edge firewall and VPN systems. The issue, tracked as CVE-2025-9242, affected how certain implementations handled IKEv2 traffic. With it, a pre-authentication attack surface could be created in systems often used for remote access and site-to-site connectivity.

The vulnerability was disclosed by WatchGuard in September 2025. Researchers analysed it publicly. Only in November 2025 was it added to CISA’s Known Exploited Vulnerabilities catalogue, meaning it had been confirmed as exploited in the wild.

That sequence matters because it marks a shift from theoretical risk to operational reality.

A vendor disclosure signals a flaw. Public research explains how it works. Inclusion in the KEV catalogue tells organisations something more direct: attackers are already using this path. At that point, patching alone isn’t enough.

When Nokia Missed the Pivot

How slow bets on Symbian and Windows Phone ceded smartphones to Apple and Android, forcing Nokia into a radically different role.

When an internet-facing gateway is exploited, teams have to look beyond updates. They have to question how VPNs and tunnels are configured, how exposed those gateways really are, and whether monitoring and assumptions still hold. The focus moves from fixing a bug to reassessing trust at the edge.

That’s when tools that examine protocol behaviour come back into focus.

yIKEs fits that pattern. It became relevant when events reminded organisations that the IKEv2 layer is still a valid path to initial access. And attackers target edge devices because of what they can reach and what they’re trusted to do, not because defenders are careless or unaware of them.

When real-world attacks target foundational layers, the tooling that examines them gets dusted off again. That’s the context behind yIKEs’ renewed visibility. And it’s why dismissing it as a niche research artefact misses the underlying enterprise lesson.

The Real Issue: Legacy Protocols Never Left the Building

Calling IKEv2 “legacy” creates distance that doesn’t exist.

In most enterprises, it isn’t an old system waiting to be decommissioned. It’s active. It’s embedded. And it’s often central to how environments function.

Hybrid architectures rely on it by design. Site-to-site tunnels connect data centres to cloud platforms. Partner access relies on long-standing IPsec agreements. Remote access still flows through VPN gateways, even when identity-based access exists elsewhere. Mergers and acquisitions introduce “temporary” connectivity that often becomes permanent.

None of this is inherently wrong.

But risk appears when the choices behind these systems become “set and forget”. Once connectivity works, it fades into the background. The rest of the security programme moves on. The edge stays quiet.

But risk appears when these components are treated as finished decisions instead of ongoing dependencies. Once connectivity works, everything related to it fades into the background. Even as the rest of a security programme evolves.

How Security Debt Accumulates Below the Application Layer

Most security investment is easy to see. Identity platforms. Endpoint controls. Cloud posture tools. Monitoring systems. They’re visible and easy to position as progress.

Inside Modern Network Design

Map the hardware, protocols and topologies that underpin resilient enterprise connectivity, from office LANs to smart city infrastructure.

Protocol-layer risk builds differently.

It sits below applications. Below identity controls. And often below daily attention. Over time, assumptions replace checks. Stability starts to look like safety. And that’s how security debt forms at the edge.

Why “encrypted” doesn’t mean “low risk”

Encryption protects data confidentiality. It doesn’t eliminate exposure.

Encrypted tunnels still depend on negotiation logic, authentication steps, and vendor-specific implementations. Weaknesses here often have nothing to do with cryptography. Pre-auth behaviour, parsing logic, and error handling have all been used to attack edge devices.

When something breaks at this layer, the impact is wide. A compromised gateway doesn’t just expose one app. Because it sits at a trust boundary with broad network reach.

Why protocol-layer risk is easy to ignore in large organisations

This category of risk is organisationally awkward.

Responsibility is often split across network teams, infrastructure, security operations, and external providers. Reviews focus on uptime and patching, not on whether the underlying assumptions still hold true. Visibility into encrypted paths is limited. And performance concerns often discourage experimentation or deeper inspection.

Over time, foundational connectivity stops being examined through the same risk lens applied to applications or identities. It becomes plumbing, even though it enforces some of the most important access decisions in the environment.

Why This Still Matters in Zero Trust and SASE Environments

Zero Trust and Secure Access Service Edge aren’t new concepts. In fact, in most enterprises they’re already policy. So they’re embedded in strategy documents, operating models, and board-level conversations about how access risk is managed.

What hasn’t changed as cleanly is the connectivity underneath it all.

When Data Breaches Meet Proxies

Assess how proxy strategy can mitigate large-scale data compromise, limit blast radius and reduce exploitable attack surfaces.

Even organisations that see themselves as “Zero Trust mature” or “SASE-aligned” still rely on VPN gateways, site-to-site tunnels and inherited edge infrastructure. They may have been forgotten about, but they haven’t disappeared. They’ve just been absorbed into a broader access model, often with less direct scrutiny than before.

That’s where risk quietly reshapes itself.

When Zero Trust becomes the main mental model, it’s easy to assume older access paths matter less. Or that identity controls compensate for weaknesses elsewhere. In reality, those paths still enforce trust decisions of their own, sometimes outside the visibility and governance applied to more modern access models.

The result isn’t a temporary transition problem. It’s a structural one. Security leaders can believe risk is being reduced because policy has advanced. But the truth is that foundational connectivity is still governed by assumptions made years earlier. And without active oversight, Zero Trust and SASE can coexist with those inherited access models.

Which means those older risks are still there, waiting to be exploited.

That’s why protocol-layer scrutiny still matters. Not because organisations haven’t modernised, but because modern access strategies don’t automatically neutralise the behaviour of the infrastructure they sit on.

What CISOs Should Be Asking About Inherited VPNs and Gateways

The real value of moments like this lies in the questions they prompt.

Visibility and ownership

Clear accountability matters.

- Who owns each VPN gateway and site-to-site tunnel?

- Which connections are critical to the business?

- Which exist only because they always have?

- When were these paths last reviewed as security decisions, not operational details?

When ownership is unclear, risk fades into the background.

Validation over assumption

Stability isn’t validation. Neither is compliance with a standard.

Continuous validation means understanding how gateways behave during authentication and negotiation. Not just whether they’re patched. It means testing assumptions about trust boundaries instead of just relying on the fact that traffic is encrypted.

The existence of tools like yIKEs reflects that need. They’re a response to repeated evidence that protocol-level behaviour still matters.

Managing transition without compounding risk

When DNS Becomes Strategy

How selecting public DNS now affects speed, resilience, privacy and governance in increasingly distributed digital estates.

Modernisation increases certain responsibilities. For a time at least.

So security leaders should know which legacy access paths remain, how they’re monitored, and when they’ll be retired or redesigned. Without that clarity, temporary coexistence becomes permanent exposure.

Final Thoughts: Legacy Risk Hides Where Modernisation Pauses

yIKEs has drawn attention because it highlights an uncomfortable truth. Which is that enterprise security still depends on long-lived assumptions about the network edge, even as access strategies evolve. So the lesson isn’t that older protocols are unsafe by default. It’s that foundational layers are easy to stop questioning precisely because they keep working.

The next phase of security leadership won’t be defined by who adopts new models fastest. It’ll be defined by who modernises without leaving quiet, high-impact risks untouched. And that’s the gap EM360Tech continues to focus on, bringing expert-led analysis to the places where industry narratives move on faster than the infrastructure they rely on.

Comments ( 0 )