If 2024 was the year AI became unavoidable, 2025 was the year it stopped behaving like a bounded tool.

Many enterprise teams went into the year assuming AI would follow familiar patterns. Pilot it, approve it, scale it. Put policies around it. Keep the risky parts contained inside a small number of sanctioned platforms. Treat it as a capability you can “add” to products and processes without changing how the organisation runs.

That illusion did not survive.

AI started acting more like infrastructure. It showed up everywhere, often through third-party platforms, sometimes through well-meaning teams moving faster than governance could keep up. The risk profile shifted, the regulatory pressure sharpened, and the real limiting factor for scaling AI became the thing most enterprises have been struggling to fix for a decade: data.

These five moments explain why enterprise AI adoption now looks less like a feature rollout and more like a redesign of AI operating models, AI governance, and AI risk management going into AI strategy 2026.

AI Escaped Central Control With the Rise of Agentic Systems

For a while, enterprise AI felt like a better interface. You asked, it answered. You prompted, it suggested. Even when the output was wrong, the failure mode was familiar. A human still had to act.

Then the centre of gravity shifted.

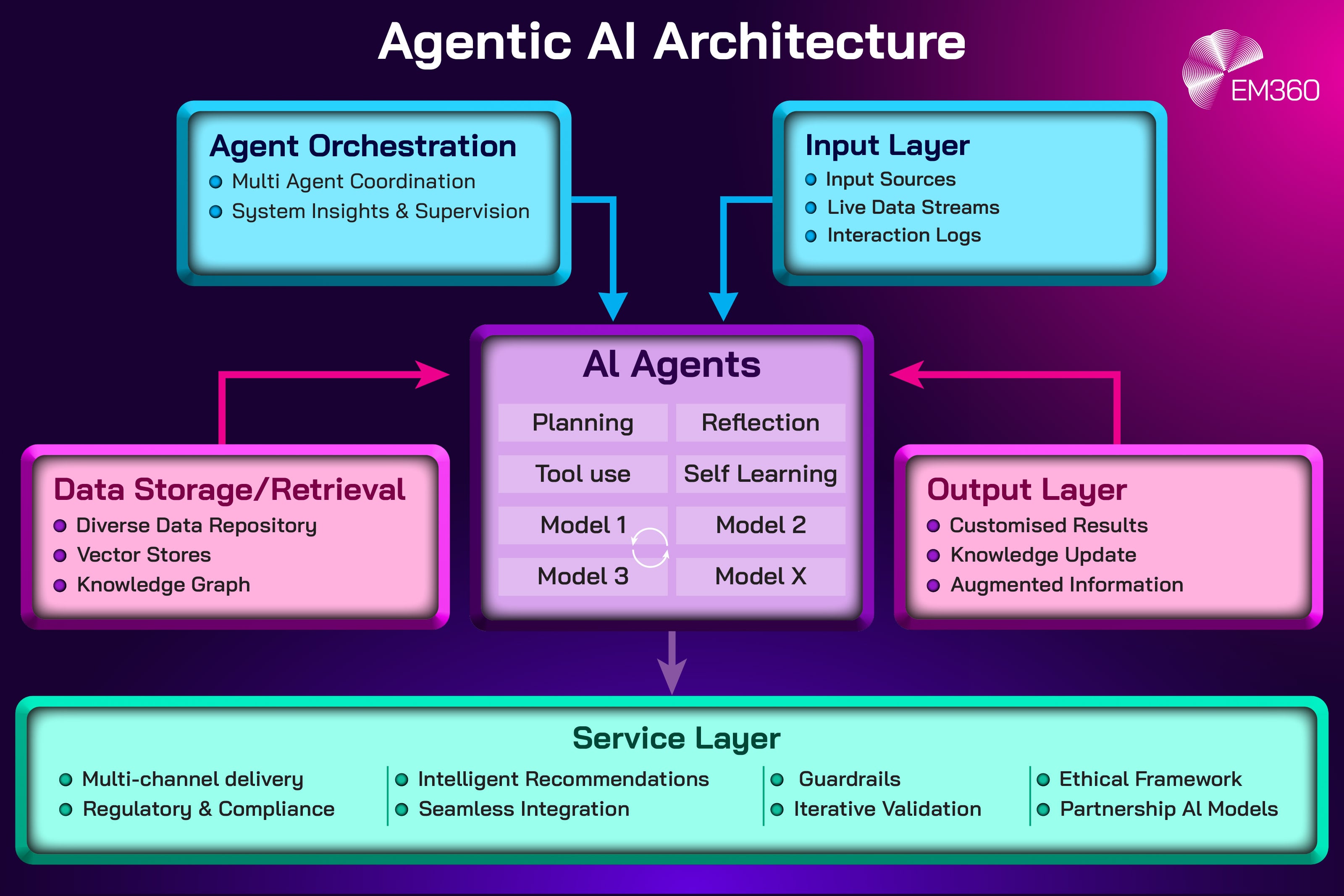

Agentic AI refers to systems that can take actions, chain tasks, and interact with tools or other systems with minimal human input. In practical terms, that means AI is no longer only generating text or summaries. It is starting processes, moving information between systems, making recommendations that trigger real outcomes, and operating inside everyday enterprise workflows.

This shift mattered because it broke a comfortable assumption: that AI could be centrally reviewed, approved, and contained like traditional software. With AI agents embedded into developer tools, security platforms, and SaaS products, “approved AI” stopped being a single decision. It became a moving target.

Once AI can act, the risk model changes. It is not just about whether a response is correct. It is about whether the system can be trusted to behave safely when it has access to real tools, real data, and real permissions.

How enterprises reacted in the moment

The first enterprise response was not panic. It was friction.

Teams realised that existing approval processes did not map cleanly onto autonomous AI systems. Security reviews often assume fixed functionality. Governance reviews often assume stable boundaries. Procurement assumes a product is a product, not a capability that can mutate as vendors add more automation and tool access.

As agent-like features arrived through platforms that were already in use, many organisations faced a choice they did not like. Either slow down the business by blocking upgrades and features, or accept that agentic capabilities would arrive faster than central control models could manage.

That created a new category of operational actor. AI was no longer just a user tool. It started to look more like a system user with agency, which immediately raised uncomfortable questions around oversight and accountability.

What this forces enterprises to do differently in 2026

In 2026, the winners will stop treating agentic capability as a policy problem and start treating it as an architecture problem.

Usage policies still matter, but they will not be enough. Enterprises will need control designs that assume AI can act. That means planning for AI identities with defined lifecycle management, AI permissions that align to least privilege, and AI monitoring that makes agent behaviour visible, auditable, and explainable enough to manage.

When Platforms Betray Communities

How ownership changes, ad demands and moderation choices turned a creative social hub into a case study in misaligned platform strategy.

It also means building containment into the operating model. Whether you call it a safety mechanism, a rollback path, or an AI kill switch, the intent is the same: when autonomous behaviour goes off-script, the organisation needs the ability to pause, isolate, and recover quickly.

This is why agentic AI is already reshaping budgets. You do not “bolt on” AI risk controls after the fact. You fund them the way you fund identity, security engineering, and resilience.

AI Regulation Became an Operational Reality, Not a Future Debate

For years, AI regulation lived in the future tense. Enterprises talked about principles, ethics, and responsible use, often without the urgency that changes operating models.

That changed when regulatory timelines and enforcement expectations became concrete.

Europe has been the forcing function, but the shift is global in effect. When one major jurisdiction moves from discussion to enforceable requirements, global organisations have to respond. They cannot run one standard in one region and a completely different standard elsewhere if they want to scale AI safely.

The deeper change is not just “more rules”. It is what those rules demand. AI regulation is increasingly tied to operational realities like documentation, accountability, and auditability. In other words, it is not enough to say you are responsible. You have to prove it.

That puts pressure on how AI systems are built, governed, and monitored, especially when you are working with third-party models, embedded capabilities, and distributed teams.

How enterprises reacted in the moment

Enterprises moved from principles to programmes.

This is where AI compliance stopped being an ethics conversation and started becoming a cross-functional operating agenda. Legal teams needed clarity on obligations. Security teams needed clarity on risk boundaries. Data teams needed clarity on provenance and lineage. Engineering teams needed clarity on documentation and change control. Compliance teams needed evidence.

Engineering Continuous Compliance

Use cloud-native tooling, GRC platforms and pipelines to codify controls, centralise evidence and keep multi-cloud architectures audit-ready.

Organisations that were already strong in governance found it easier to adapt. They could reuse patterns from privacy and security programmes: ownership, controls, evidence, and audit trails. Organisations that were used to informal innovation pathways discovered that informal does not survive inspection risk.

This is also where many enterprises began aligning AI governance to existing enterprise frameworks, not because frameworks are fashionable, but because they make complex requirements operational.

What AI compliance looks like heading into 2026

The biggest 2026 change is mindset.

AI compliance will not sit under “innovation”. It will sit alongside security, privacy, and enterprise risk. That changes the budgeting conversation. It changes the reporting conversation. It changes how quickly “we are piloting” turns into “we need controls”.

Inspection-readiness becomes the default posture. Enterprises will be expected to demonstrate AI accountability in a way that holds up under external scrutiny. That includes documentation, decision logs, model and data governance, and clarity on who is responsible for what.

The practical takeaway is simple: AI auditability is now a design requirement. If your AI operating model cannot generate evidence, your compliance posture is built on hope.

Shadow AI Moved From Suspicion to Proven Enterprise Risk

Shadow AI is not a dramatic term. It is a plain description of what happens when people use AI tools outside official approval channels.

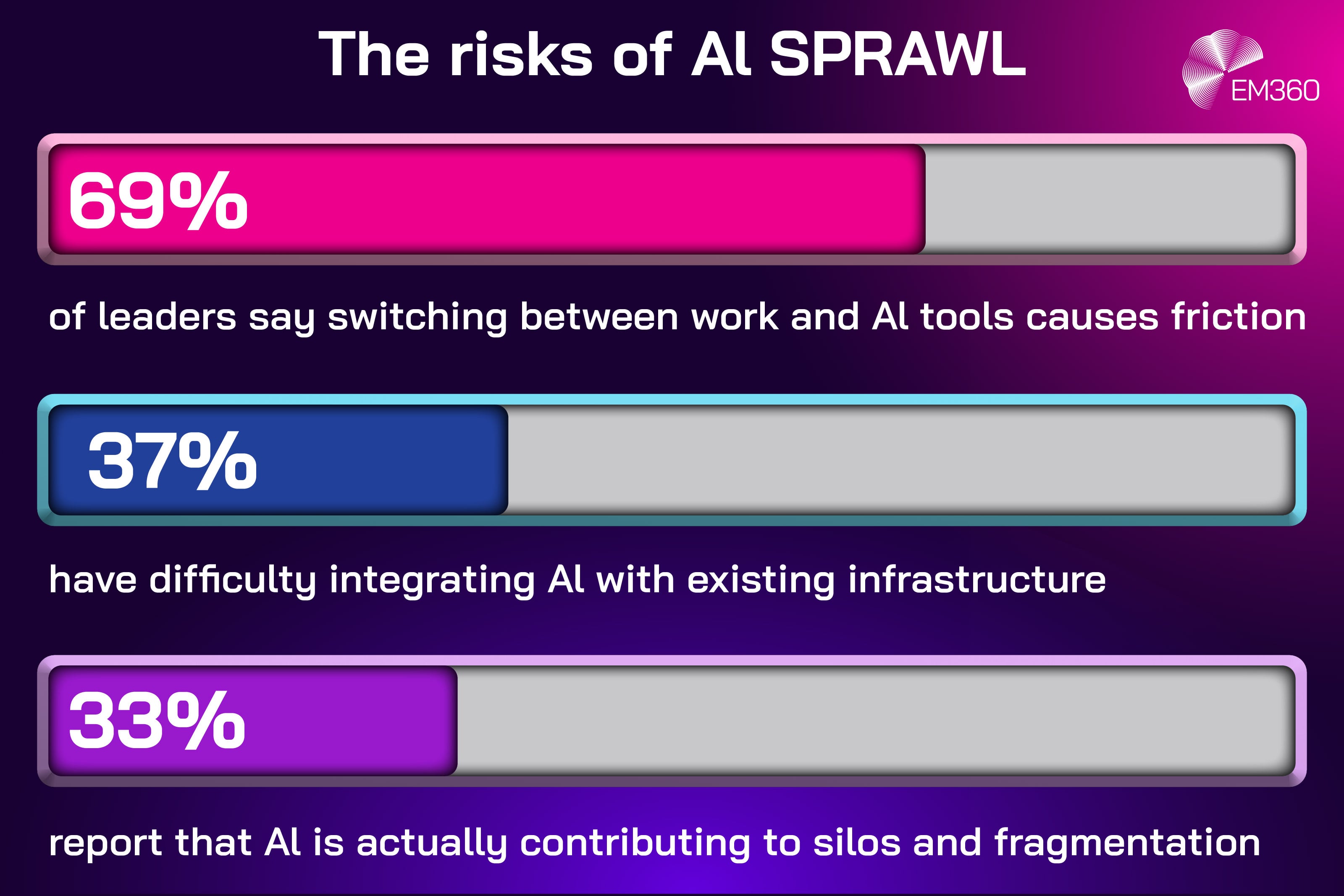

In 2025, shadow AI became undeniable because AI stopped being optional and started being embedded. Employees used public tools to move faster. Teams tried new assistants to cut repetitive work. Departments switched on AI features inside platforms that were already contracted. Some groups built internal automations without waiting for central governance, because the business incentives favoured speed.

This created AI sprawl that looked familiar in shape, but not in tempo. It resembled SaaS sprawl and cloud sprawl, just faster and harder to see. Even well-run enterprises discovered they did not have a reliable map of where AI was being used, what data was being shared, or what outcomes AI decisions were influencing.

Data Control Lessons from Google+

Uses the Google+ shutdown and Project Strobe review to explore privacy expectations, API governance, and consent in large-scale platforms.

That is the moment the conversation changed. The risk was not hypothetical. It was operational.

How enterprises reacted in the moment

Blanket bans failed in practice, even when they looked clean on paper.

If you block everything, people still find workarounds. If you allow everything, you lose control over data exposure and decision quality. Most enterprises ended up in the middle, not because it is comfortable, but because it is the only workable reality.

The first serious response was visibility. Organisations began focusing on AI discovery and AI visibility as foundational capabilities. You cannot govern what you cannot see.

At the same time, enterprises started reframing the problem. Shadow AI is rarely an employee misconduct issue. It is often a signal that official pathways are too slow, too restrictive, or do not meet real workflow needs. If the organisation wants sanctioned adoption, it has to make the sanctioned route easier than the unsanctioned one.

Governing reality instead of policy ideals in 2026

In 2026, mature enterprises will stop asking, “How do we stop people using AI?” and start asking, “How do we make safe AI use the default?”

That is a governance maturity shift. It means accepting that enterprise AI usage will be distributed, then investing in guardrails that reduce harm without crushing productivity. It also means designing policies that reflect how people actually work, not how governance teams wish they worked.

Expect more investment in AI control measures that focus on mapping usage, protecting data, and constraining risk. That includes standardising approved toolsets, implementing data protection controls, and building a governance process that can keep pace with product updates and new embedded capabilities.

This is what “govern reality” looks like: fewer debates about ideology, more focus on AI risk mitigation that works under real-world conditions.

Data Foundations Replaced Models as the Limiting Factor for AI

When Social Feeds Add AI

How embedding chatbots into social apps is changing user engagement, data collection and safety expectations on youth-focused platforms.

For a long time, the AI conversation was model-led. Bigger models, better reasoning, improved output quality. Many enterprises assumed that if they chose the right model, AI value would follow.

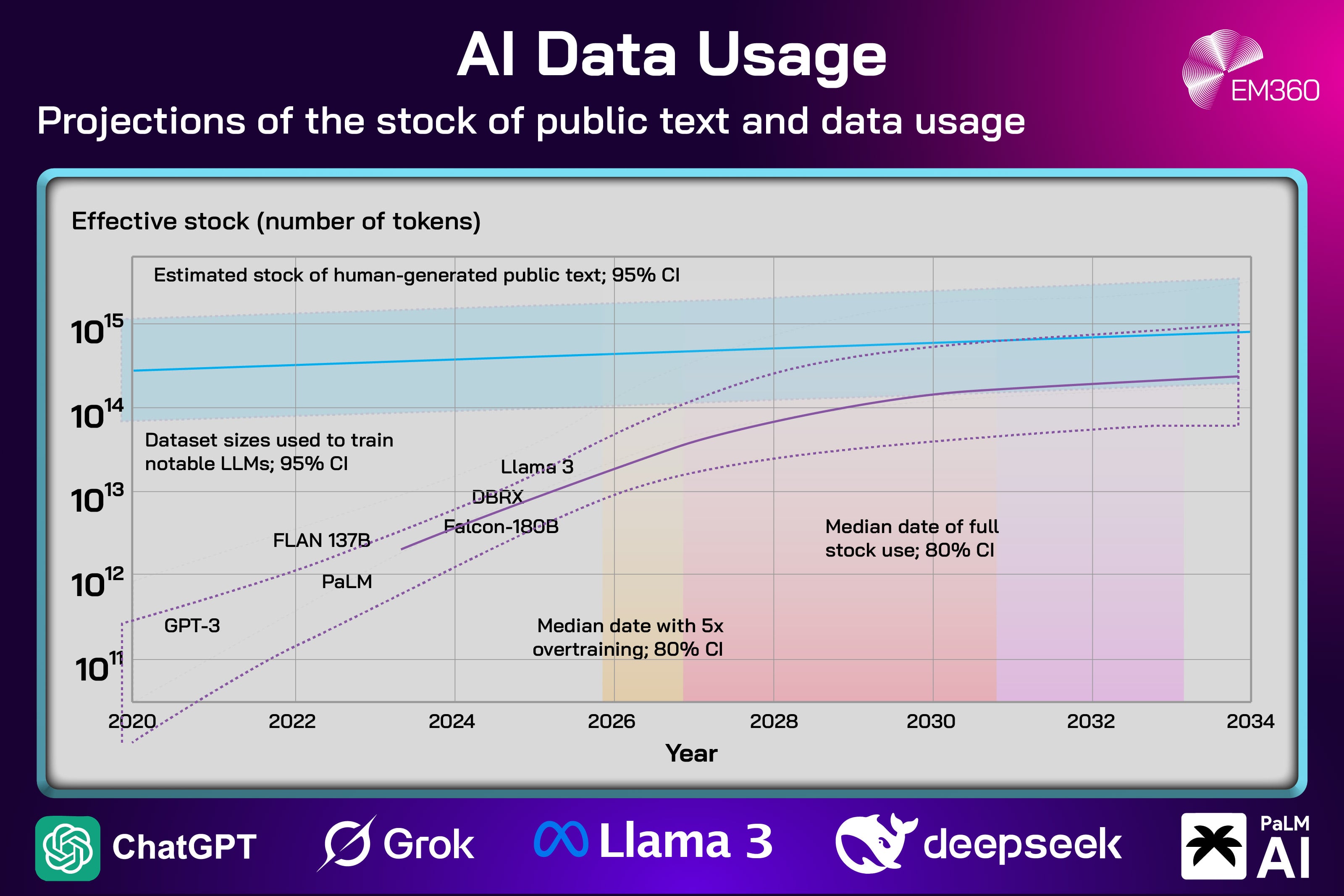

Scaling exposed a harder truth: AI success is increasingly constrained by data.

As deployments expanded, organisations ran into limits around quality, lineage, ownership, and sovereignty. The bottleneck was not whether a model could generate a convincing answer. It was whether the enterprise trusted the data feeding the system, and whether the organisation could prove that trust was justified.

This is where AI data readiness stopped being a vague aspiration and became a measurable prerequisite. If your data is inconsistent, poorly governed, or difficult to trace, your AI outcomes will be unreliable. Worse, they will be difficult to defend.

That is the operational difference between “AI pilots” and “AI that the business can rely on”.

How enterprises reacted in the moment

Many enterprises discovered their AI programmes were outrunning their data foundations.

Pilots stalled. Scaling was slow. Teams could not agree on what the “right” data source was. Ownership was unclear. Data quality problems that were tolerable in dashboards became unacceptable when they drove automated decisions.

This forced a reprioritisation. Data teams, governance teams, and platform teams moved from the edges of AI programmes to the centre. Organisations started treating data governance and data quality as AI enablers, not back-office hygiene.

It also exposed how easy it is to overestimate readiness. “We have data” is not the same as “we have data we trust, with known provenance, with clear usage rights”.

Why AI strategies in 2026 start with data, not models

In 2026, the most effective enterprise AI strategy 2026 approaches will begin with the foundation question: what data can we trust, and what do we need to fix before we automate decisions at scale?

This is why budgets will continue shifting toward enterprise data governance, data platforms, and visibility layers like data observability. It is not a detour away from AI. It is the work required to make AI dependable.

This also connects directly back to compliance and risk. If you cannot trace data lineage, you cannot defend your outputs. If you cannot define ownership, you cannot assign accountability. If you cannot ensure data quality, you cannot scale safely.

The model matters, but the model cannot save you from messy foundations. AI scaling is increasingly a data discipline.

AI Risk Escalated to the Boardroom

At a certain point, AI stopped being framed as an innovation advantage and started being treated as an enterprise risk category.

That shift was driven by three pressures that boards understand intuitively: reputational impact, regulatory exposure, and operational risk. High-profile failures made it easier to imagine downside. Regulatory timelines made it harder to postpone governance. The operational spread of AI made it clear that “the AI team” cannot own the entire blast radius.

Once that happens, AI risk joins the same governance lane as cyber risk and legal risk. It becomes a leadership issue, not just a technical issue.

This is not a sign that boards want to micromanage AI. It is a sign that AI is becoming business-critical enough to demand structured oversight.

How enterprises reacted in the moment

Enterprises began formalising ownership.

That often looked like new reporting lines, executive sponsorship, and clearer boundaries between innovation teams and risk owners. It also looked like governance structures that can handle trade-offs: when do we accelerate, when do we constrain, and who is accountable for the consequences?

Many organisations pulled AI oversight into existing structures like risk committees or audit committees, because those structures already know how to manage complex, cross-functional exposure. The mechanics are familiar: reporting cadence, metrics, control testing, and escalation paths.

This is governance maturity showing up in organisational design.

What AI ownership and accountability look like in 2026

In 2026, the strongest organisations will focus on formalisation, not centralisation.

AI ownership will be clearer, but it will not be a single “AI czar” controlling everything. Mature models will assign accountability where it can be acted on: product owners for product behaviour, security leaders for access and controls, data leaders for governance and provenance, and executives for risk acceptance decisions.

Expect more standardisation around AI leadership practices, including defined roles, reporting structures, and frameworks that connect AI outcomes to enterprise risk.

The key point is this: when oversight reaches the boardroom, AI stops being a side project. It becomes part of how the enterprise is governed.

Final Thoughts: Control Was the Illusion, Governance Is the Work

The most important lesson enterprises carried out of 2025 is not that AI moved faster than expected. It is that many organisations were optimising for a kind of control that no longer exists.

AI no longer sits neatly inside approval workflows or innovation roadmaps. It acts, connects, scales, and embeds itself through platforms, data flows, and everyday decisions. Regulation has caught up enough to make that reality enforceable. Shadow usage has made it visible. Data constraints have made it unavoidable. Board oversight has made it non-negotiable.

What replaces control is not restriction. It is governance that assumes movement, autonomy, and change. Governance that is built into operating models rather than layered on after the fact. Governance that treats AI as part of the enterprise system, with the same expectations around accountability, evidence, and risk as any other critical infrastructure.

That is why enterprise AI strategy going into 2026 looks less like experimentation and more like design work. The organisations that move with confidence will be the ones that stopped asking how to contain AI, and started asking how to run it responsibly at scale.

For enterprise leaders navigating that shift, staying grounded matters. EM360Tech exists to track these inflection points as they happen, connecting AI governance, risk, and strategy in a way that reflects how enterprises actually operate, not how we wish they did.

Comments ( 0 )