AI is no longer a “pilot programme” happening in a corner of the business. It is in support workflows, developer tooling, security operations, and decision-making, often all at once. Some of it is sanctioned. A lot of it is not. Either way, it is happening because it is useful and because the productivity upside is hard to ignore.

That creates an uncomfortable truth for AI security leadership: bans and blanket “no AI” policies are not holding. They are simply pushing usage out of sight. The real risk is not AI itself. The risk is unmanaged AI, adopted faster than the organisation can control it.

As we head into 2026, enterprise leaders are facing an inflection point. Governance can catch up to that reality, or the gap between adoption and control becomes the next self-inflicted incident class.

AI Adoption Has Outpaced Governance

The data is blunt. In Delinea’s 2025 survey of 1,758 IT decision-makers, 94% of global companies report they use or pilot some form of AI in IT operations. At the same time, only 44% say their security architecture is fully equipped to support secure AI today.

That is the AI governance gap in practical terms: adoption is already mainstream, while readiness is still uneven.

EY’s Responsible AI Pulse survey points to the same pattern at the executive level. EY reports that 72% of executives say their organisations have “integrated and scaled AI” in most or all initiatives, and 99% are at least in the process of doing so. Yet only a third have the protocols in place to adhere to all facets of EY’s responsible AI framework.

It is tempting to read this as negligence. It is usually not. Most organisations are trying to do the right thing. The problem is structural: enterprise AI adoption is expanding across functions faster than governance models can be designed, operationalised, and enforced.

Why This Gap Keeps Repeating and Why AI Raises the Stakes

Every major platform shift creates a lag between what employees can do and what the organisation can govern. Wi-Fi, mobile, cloud, then SaaS. The pattern is familiar: first comes adoption, then comes standardisation, then comes control.

AI disrupts that order because it does not just expand access. It expands agency.

A traditional application is a tool a human uses. Many modern AI systems, especially agentic systems, can initiate actions, chain tasks together, and operate across systems with limited human friction. That changes the risk profile from “someone used the wrong tool” to AI operational risk that looks like business process risk.

In Delinea’s data, 56% of organisations actively use both generative AI and agentic AI in IT operations. That combination matters. Generative AI can help a person move faster. Agentic AI can help a system move faster, and sometimes without waiting for a person.

When governance fails in that environment, it is not only a compliance problem. It becomes an operational one. Workflows break. Controls drift. Accountability gets blurred. That is why executives cannot wait for governance to “settle.” It will not settle on its own.

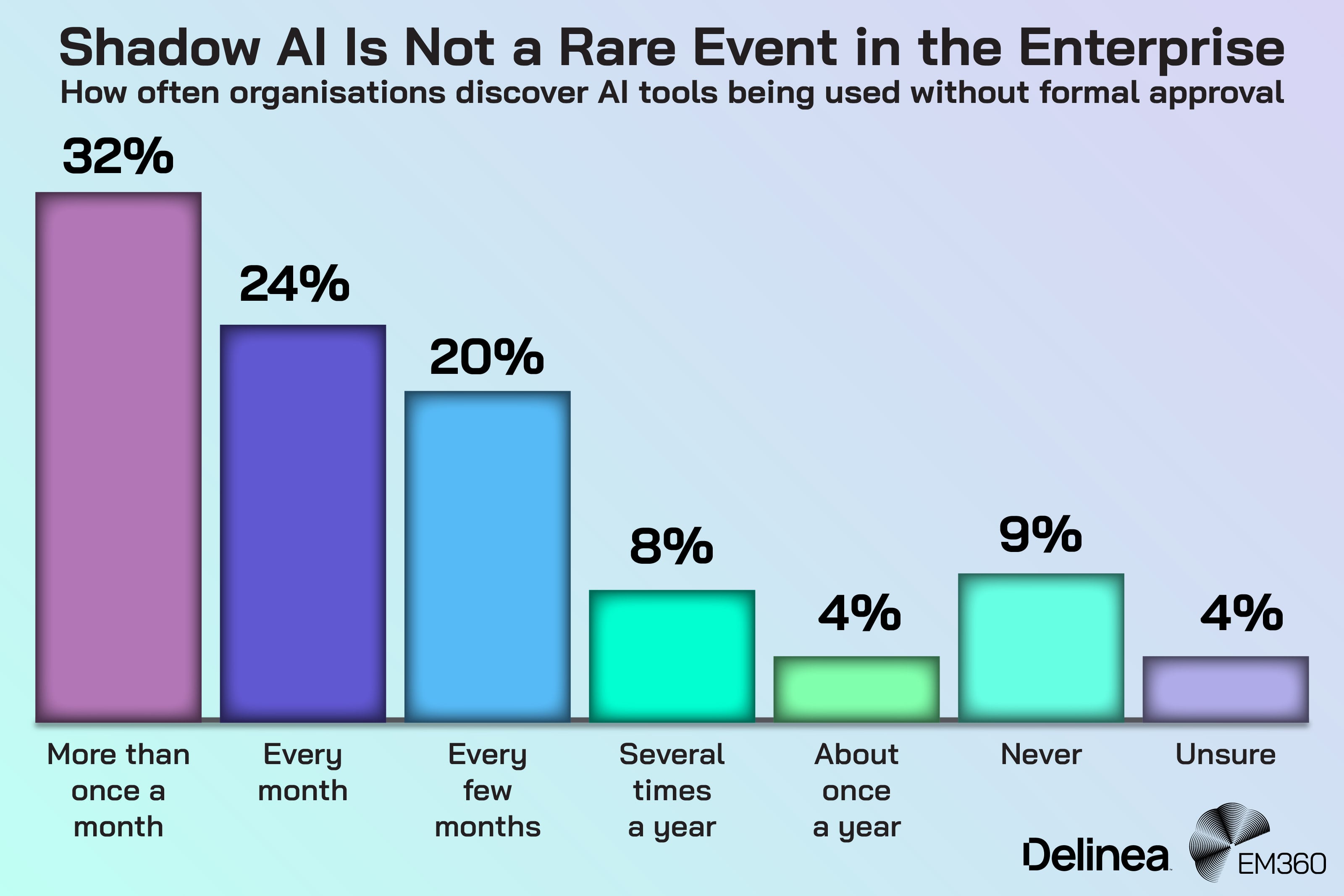

Shadow AI Is No Longer Edge Behaviour

Shadow AI is often framed as reckless behaviour by employees. The data suggests something more ordinary: it is a visibility problem.

Delinea found that 59% of organisations run into shadow AI issues at least monthly. In other words, unsanctioned usage is not rare, it is routine.

Identity-Led AI Governance

Why CISOs are making identity the primary control plane to close AI adoption gaps and align governance, access, and security operations.

Immuta’s research helps explain why. In its AI Security and Governance survey, Immuta highlights the speed of adoption and the scale of usage. It notes that more than half of data experts say their organisation already leverages at least four AI systems or applications, and that 79% report increased budget for AI systems, applications, and development in the last 12 months.

This is what makes shadow AI hard to “policy away”. Knowledge workers will use tools that make them faster, especially when the business rewards speed. Developers will adopt what improves throughput. Teams will pick up whatever removes friction. If governance only shows up as a blocker, people route around it.

The consequence is not just unsanctioned tooling. It is governance blind spots across:

- data exposure through prompts and outputs

- untracked models and vendors

- inconsistent controls between teams

- unclear accountability when something goes wrong

If 2026 governance starts with enforcement instead of visibility, it will fail. You cannot govern what you cannot see.

Identity Has Become the Control Plane for AI

Most governance conversations still focus on models and data. Those are essential, but they are not enough in an agentic world.

AI systems increasingly behave like actors in the environment. They request access, execute tasks, interact with data, and sometimes trigger changes. Treating them like “just another app” is a category error. They are closer to machine identities than applications, and they need to be governed with the same seriousness as privileged users.

Delinea’s report makes this explicit. It argues that as organisations deploy AI, they must begin treating those entities with the same level of scrutiny and governance as privileged employees, contractors, or partners.

The governance implication is straightforward: AI access controls cannot be bolted on at the end. Identity, access, and privilege design become foundational to AI security governance, especially as agents move from assisting humans to acting on their behalf.

Identity-First AI Control

Why separating human and machine identities is now core to governing agents, privileged access and AI workloads across cloud and SaaS.

This also connects directly to responsible AI operationalisation. Responsible AI fails when it lives only in principle statements and committee decks. It works when it shows up as concrete controls in build and deployment workflows, including who or what can access sensitive systems, what they can do, and how actions are logged and reviewed.

Agentic AI Turns Governance Into a Continuous Discipline

Most enterprise governance models still assume periodic review cycles like annual policy refreshes, quarterly risk reporting, and occasional audits. That cadence made sense when systems were relatively stable.

Agentic AI does not operate on that timetable.

When AI can initiate actions, governance becomes a control loop, not a document. Controls need to be measurable, monitored, and updated as usage evolves. This is less about writing better policy and more about building governance that can keep up with real behaviour.

PwC’s 2025 US Responsible AI Survey underlines this shift toward execution. PwC reports that about six in ten respondents (61%) say their organisations are at either the strategic or embedded stage, where responsible AI is actively integrated into core operations and decision-making. That progress is real, but it also implies a widening gap between organisations that operationalise governance and those still stuck in early-stage frameworks.

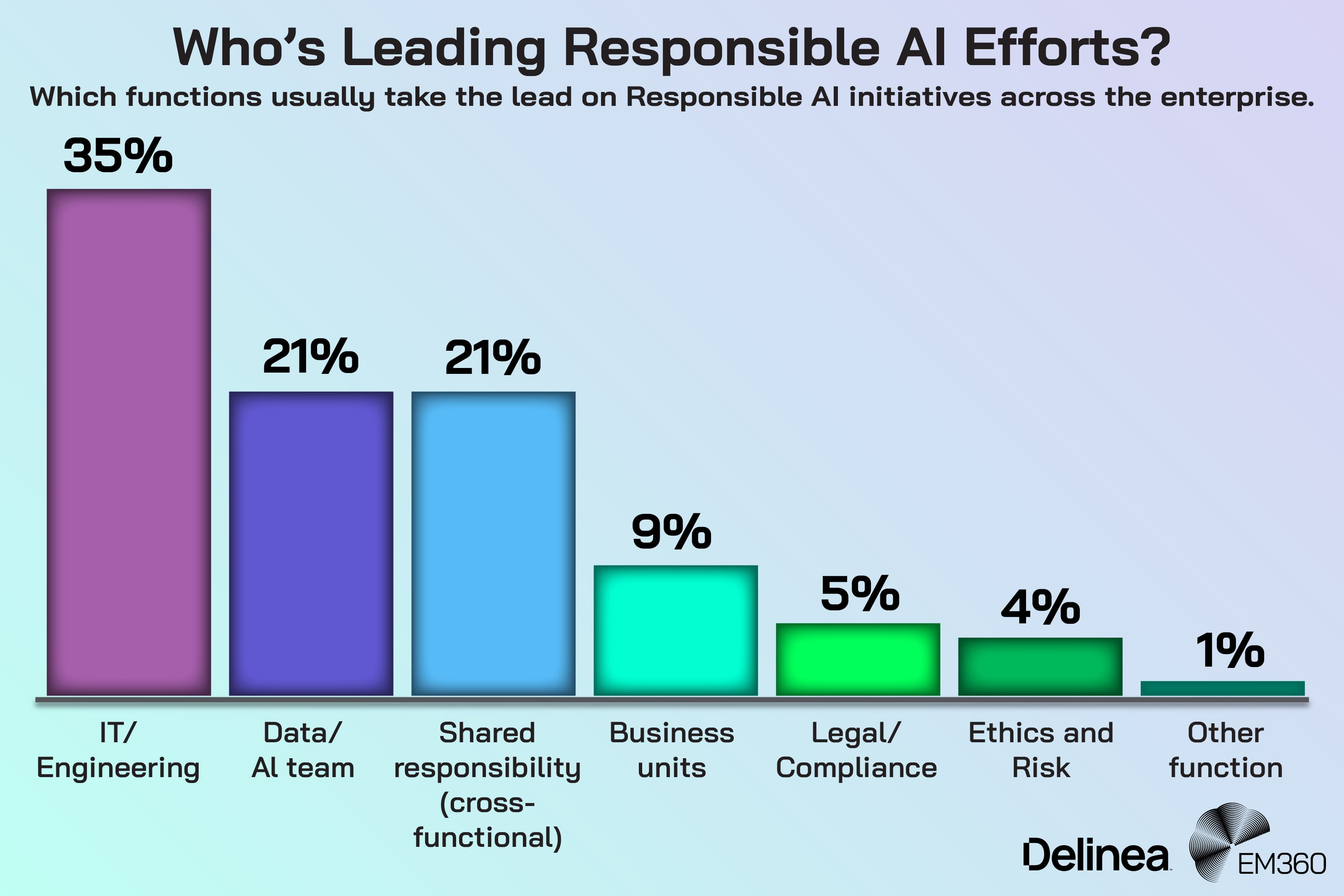

PwC also notes a move in ownership. 56% of executives say first-line teams such as IT, engineering, data, and AI now lead responsible AI efforts, putting governance closer to where systems are built and decisions are made. This is a practical response to the agentic problem: governance cannot keep pace if it is owned only by second-line functions, because second-line review cannot be the only throttle.

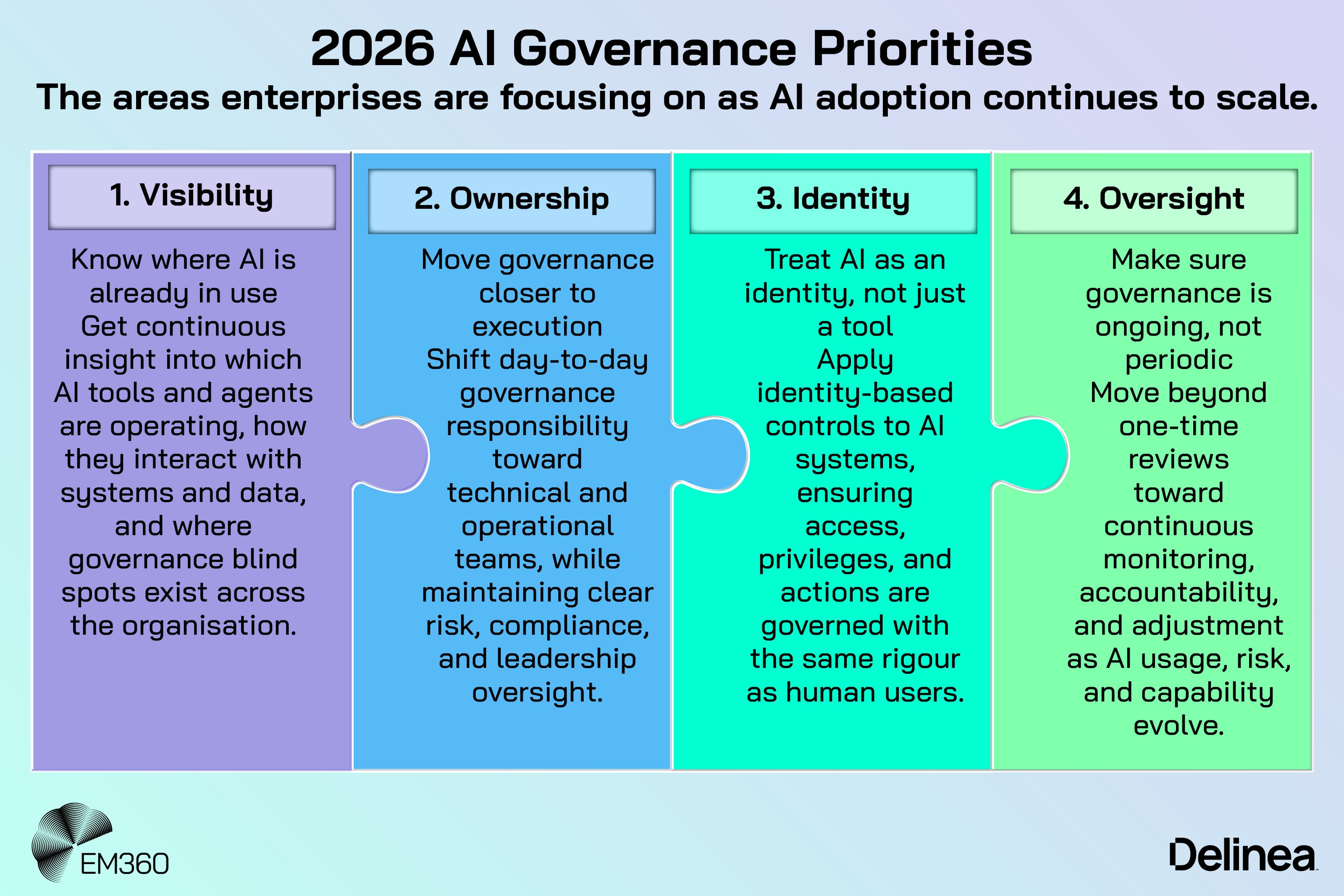

What Closing the Gap in 2026 Actually Requires

The organisations that close the governance gap in 2026 will not do it by producing a thicker policy binder. They will do it by changing how governance works day to day.

Governance must move closer to execution

If responsible AI governance lives only with legal, compliance, or a central committee, it will become a bottleneck. The business will move anyway. The result will be shadow usage and uneven controls.

When AI Agents Meet Governance

Explores how Qwen’s agentic model amplifies identity, access, jurisdiction and durability risks in enterprise AI strategy.

The better pattern is shared accountability, with clear ownership where AI is built and deployed. PwC’s findings support this direction, with first-line teams increasingly leading responsible AI efforts. This does not remove oversight. It makes oversight scalable, because the teams doing the work can also own the guardrails.

Visibility before restriction

Governance programmes that start with prohibition often end with ignorance. The goal is not to catch people out. The goal is to establish a realistic picture of how AI is actually being used.

Delinea’s finding that shadow AI issues occur at least monthly for a majority of organisations makes visibility a governance prerequisite, not a nice-to-have. Discovery, monitoring, and inventory are the difference between governing reality and governing a spreadsheet.

Governance as a management system, not a policy document

AI governance needs lifecycle thinking. Risk changes as models, tools, and workflows change. Controls need regular testing and adjustment, not just approval.

Immuta’s report shows how many organisations are already updating internal privacy and governance guidelines in response to AI adoption, alongside practices like AI risk assessments and monitoring outputs for anomalies. That direction matters because it moves governance from static intent to operational discipline.

The organisations that win in 2026 will treat governance as a living system, grounded in measurable controls, clear ownership, and continuous oversight.

Final Thoughts: Governance Is the Price of AI at Scale

The AI governance gap is not theoretical. Multiple surveys are measuring the same pattern: widespread adoption, rising confidence, and uneven control. Delinea’s data shows AI usage is already near-universal in IT operations while secure readiness is far from universal. EY shows executive ambition is almost total, but full governance protocols lag far behind.

2026 is the year that gap stops being a background concern and starts shaping outcomes. The organisations that treat enterprise AI governance as an operational system will move faster, with fewer surprises. The ones that treat it as a compliance exercise will keep discovering their AI footprint after something breaks.

From Tools to AI Agents

Map the seven-stage evolution from reactive systems to superintelligence and align enterprise strategy to each step of agentic maturity.

If you need a reality check on where the market stands, Delinea’s AI in Identity Security report is a strong benchmark for the adoption-versus-control gap, and EM360Tech will keep tracking the governance signals that matter to security and risk leaders as AI becomes a standard part of running the enterprise.

Comments ( 0 )