COVID-19 has been a pretty large nail in the Silicon Valley coffin. In particular, the virus necessitated a shutdown of the entire region, as infections swelled in cities with a higher population density. Then, as companies realised the perks of the work-from-home model, some of Silicon Valley’s largest businesses decided to make permanent changes and switch to the remote-first model.

However, the pandemic isn’t the only thing chipping away at Silicon Valley’s prestige. For years, residents have complained about the region’s astronomical living costs, with some resorting to living in motorhomes in the office carpark or in shipping containers.

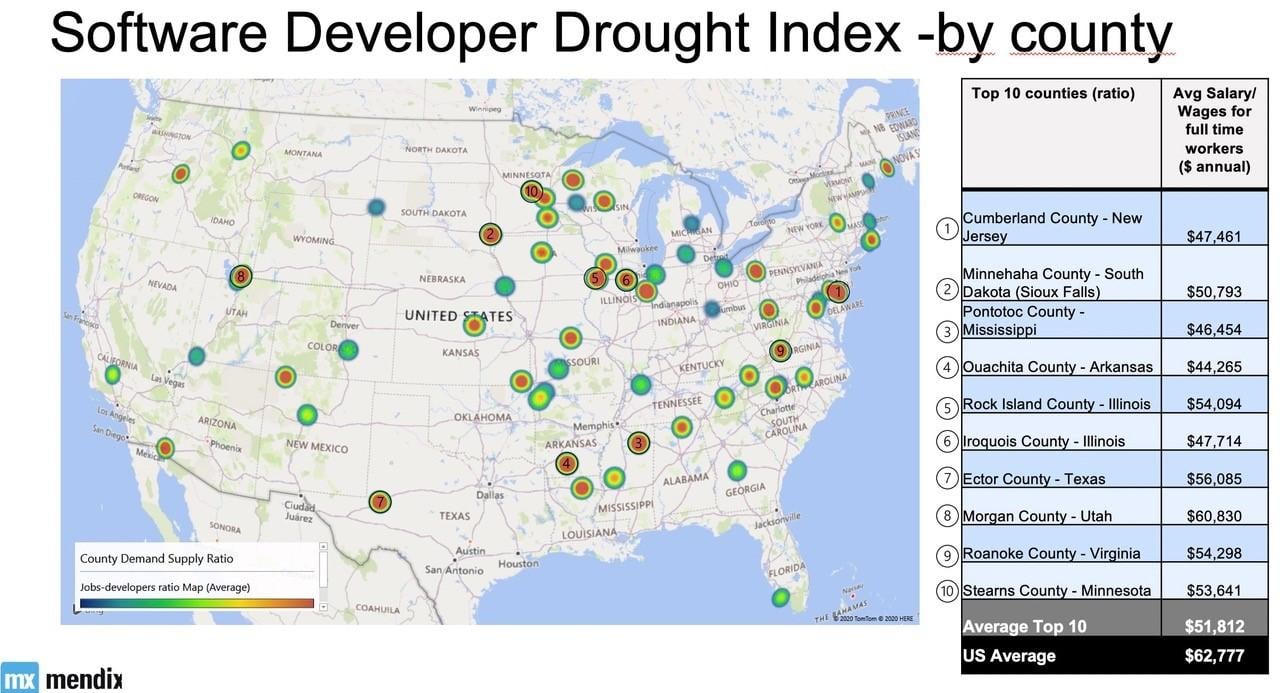

Thus, the quest for a new up-and-coming area has become all the more compelling. However, in light of the COVID-19 outbreak, the criteria has shifted to be more in favour of small, rural towns. These areas are gaining significant traction, and a testament to that is Mendix’s recent Software Developer Drought Index. In particular, the Index outlines the geography of the states with the highest developer demand, while uncovering unexpected hiring hotspots.

Eager to find out more, we spoke with Sheryl Koenigsberg, Head of Global Product Marketing at Mendix, and Laurence Evans, CEO at Reputation Leaders, to share more about the findings. Here’s what they had to say…

Thank you both so much for taking the time to speak with me! Could you firstly give us an introduction to the Software Developer Drought Index? What did it analyse?

Sheryl: For years, we’ve been hearing that there’s a developer shortage. However, a lot of the stories in the press around this shortage focus on Silicon Valley, New York City, maybe Austin, Texas – the big technical centres – yet when we looked in our customer base, we were seeing significant adoption of low code in the middle of the country and rural areas. Low code, of course, can be a good indicator for whether there’s a developer shortage because it expands who in an organisation can participate in software development. So we started to think: is this a pattern or trend that we’re seeing of developer shortages, not just in the coasts but in rural areas too?

Then, we started to see changes to how and where people were working due to COVID, and decided to do a study to investigate how the way people are thinking about staffing and the future of work is changing.

What Reputation Leaders did for us was look at US census data, which provided a sense of a region’s ability to fill jobs in IT. They gathered data that told us, ‘for every 100,000 people by county, how many people were working as IT professionals’ Then, they overlaid job openings in July/August looking for software development on the same county view. What we found was there were places in Mississippi, South Dakota, and North Carolina – places that we didn’t necessarily associate with developer drought – as places with a much higher ratio of unfilled jobs to potential candidates than some of the hotspots that we hear about in the press all the time.

Interesting! So, could you tell us a little bit more about the findings?

Sheryl: We looked at the top 10 locations where there were challenges in meeting job demand. All of them were in rural areas, like Cumberland County, New Jersey, in Mississippi, in counties in the central region of the US. Many were associated with places where major corporations had set up shop because there was some sort of incentive, like a tax incentive to the lower cost of setting up operations there.

What we found was that in places where Citibank or Wells Fargo or Paypal had set up offices – and these are not just tech companies, we’re talking cross-industry – there was then a gap when trying to attract talent to that location and get staffed up. That’s often where these challenges are.

If you think about it from the company’s perspective, they have a couple of options:

- They can try to attract young urbanites who have these skills to rural locations

- They can retrain people who are already local there

- They can expand who in the company can contribute to software development

- They can be a lot more open than they have in the past to having remote employees

If you look at what low-code enables, it’s three of those four. With something like the Mendix low-code platform, we can take somebody who was an actuary, or a paralegal, or a mechanical engineer, and turn them into a developer with a couple of months of training. We can expand the role that, say, a business analyst plays in software development. We have the collaboration tools to bridge communication between business people who may be at headquarters and developers who may be located around the country.

You’ve touched a little bit there about the incentives and benefits of these smaller, more rural areas, but could you expand on what the increasing appeal is?

Laurence: Across the top 10 developer drought counties we investigated, we found much lower rents and much lower commute times. In particular, we saw an average commute time of only 22 minutes in the top 10 cities, compared to very long commutes in the others, which shows that people are rethinking their whole work-life balance as well.

Silicon Valley is really pricing people out of the region, and then of course, some of its largest companies are operating on a remote-first basis. What does that mean for the future of Silicon Valley? Will it lose its prestige?

Sheryl: What’s most interesting to me is what the future looks like for the young part of the workforce. When I graduated from college in the late ‘90’s, the coolest thing to do was go out to Silicon Valley and get a job at a tech startup. What I think is notable now is that those opportunities aren’t only in Silicon Valley.

I don’t know that I would say it’s going to lose its prestige, but as we see more opportunities for people to work remotely and better tools for collaboration, a lot of that will lend itself to companies being able to attract the most innovative and highest value talent without being restricted from a location perspective.

What do you expect the US map of tech talent to look like in 10 years?

Sheryl: I think the sky’s the limit. I don’t think that tech talent is going to be centralised around these hotspots the way it is today. Ten years from now, if we look at a map of the US and we look at where the talent is, it could be anywhere.

Look at the last six months: we have seen a fundamental revolution in how we work. For many of us, we went home on a Friday, and on Monday morning, we all had to be experts at collaborating remotely. These tools and technologies that enable remote collaboration are now so embedded in how we do work, it’s not just going to unwind itself and go back to everybody commuting into an office.

This has all forced corporations to figure out how to work with people remotely. It’s actually really good for the workforce because people will be able to make decisions about where they live, whether they are close to family, whether they are close to nature, and whether they are in an affordable setting, and can still have that really challenging, really compelling career.

Laurence: Location will no longer be the defining factor on mobilising software developer talent. What was interesting to us was how far behind the employers were, bearing in mind that we took the three largest IT job sites in July and August, and 92% of employers were still specifying a specific location that people had to live in, work in, and report to – it’s like, in this environment? With remote working, the cloud, and collaboration? There’s no requirement to do that.

You can pick up the most skilled labour from anywhere, so I think it’s going to redraw the map, largely on the basis of skills, and not on location. Yes, there will still be pockets, obviously, because there are ecosystems around certain universities and certain areas, but I completely agree it’s going to be much more dispersed.

Comments ( 0 )