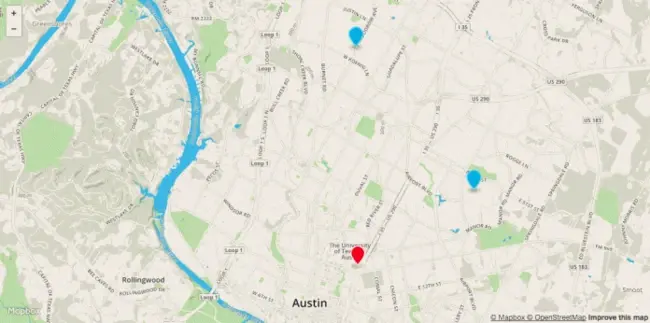

Apparently, mobile telecommunications providers in the US routinely sell users' real-time location data.

They seem to be selling it to one particular company called Securus, which ZDNet.com reports is a “prison technology company”. This enables Securus to track “any phone within seconds” from America's largest telcos, including AT&T, Verizon, T-Mobile, and Sprint. An intermediary company called LocationSmart is also involved.

While most would probably agree that it's a good way to track prisoners who have either escaped or are out on parole, it is of course theoretically possible to use such technology on innocent people who have not committed a crime and who have no idea they are being tracked.

The issue emerged as a result of a US senator sending a letter to the Federal Communications Commission demanding an investigation into Securus and any other company involved in being able to track people's movements in real-time.

What may be of more concern is that police and other “security” services are able to conduct such activities without the need to get a warrant. The situation has been called “one of the biggest gaps in US privacy law” by campaigners.

Meanwhile, in Europe, the deadline for the General Data Protection Regulation is fast approaching. By the end of this month, all companies which hold any private data on European citizens will need to have data centres in Europe which hold that data.

GDPR has a variety of provisions to try and protect the private data of European citizens, backed up by heavy fines on companies which do not conform.

However, with so many companies spending so much money on lawyers who can claim all sorts of excuses for circumventing the laws, it's unlikely that any amount of “privacy” will be reclaimed from the big tech companies.

The vast majority of people have probably given up on the idea of having a private life – thinking of it as a process of finding out how exactly how small your private space is, if it even exists.

It's interesting to note that the Facebook data set at the centre of the Cambridge Analytica scandal has apparently been available online for several years.

As New Scientist reports, data relating to millions of Facebook users who answered personal questionnaires were “left exposed online for anyone to access” for more than four years.

But the general debate about privacy and data may be encouraging a more transparent approach by tech companies.

Salesforce has appointed a data protection officer in anticipation of the May 25 GDPR deadline. And Microsoft is publicly detailing exactly what aspects of Xbox gamers' user data it plans to share with games developers and others.

Comments ( 0 )